Iranian women have been fighting for equal rights for more than a hundred years. Dress code is one of the essential components of this fight for equality. The question is why their demand to dress as they wish is not granted and even violently crushed.

We Veil our Eyes Instead of our Women’s Faces

It is not our habit to cover our faces,

Certainly, this is not part of our ways in Kipchak.

If it is your custom to cover faces,

We cover our eyes in our culture.

Instead of damaging the faces of people with a burka,

you should cover your eyes with a veil.

ولی روی بستن ز میثاق نیست

که این خصلت آیین قفچاق نیست

گر آیین تو روی بربستن است

در آیین ما چشم در بستن است

به برقع مکن روی این خلق ریش

تو شو برقع انداز بر چشم خویش

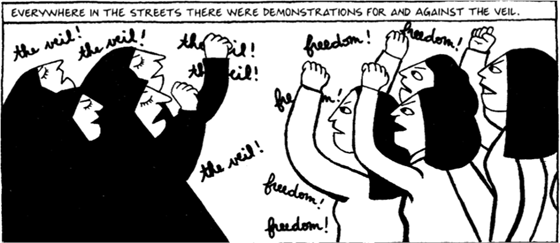

The arrest by the Iranian morality police and subsequent death in custody of the 22-year-old Ms. Mahsa (Zhina) Amini on 16 September have unleashed nationwide protests across Iran, leading to more deaths and more arrests. Iranian women have been ill-treated over the last century. They have been fighting for equal rights for more than a hundred years and dress code is one of the essential components of this fight for equality. The question is why their demand to dress as they wish is not granted by the Iranian patriarchal society and why the hijab is considered mandatory, a symbol of religious morality and chastity.

It might seem that this protest is recent, but the veil has never been uncontroversial in Iranian cultural history. From the medieval period, as the above poem by Nezami (d. 1209) shows, to the banning of the hijab in 1936 the veil has been a contentious subject. Even in Islamic mysticism (Sufism) we see that women removed their veils as a sign of protest against injustice. One example is the sister of the mystic martyr Ḥuseyn Manṣūr Ḥallāj (executed in 922). It is reported that she protested and appeared at the moment of Ḥallāj’s execution among a crowd, removing her veil. When Ḥallāj asked her from the gallows why she had removed her veil, she answered that she did not see any men, implying that all those men who had agreed to Ḥallāj’s execution and remained silent were not really men.

Another Persian woman to remove her hijab and courageously deliver lectures in public was Ṭāhirih Qurrat al-ʿAyn (executed in 1852). She set the example, and from this time onwards we see a wave of writings on the significance of the veil and why a woman should be veiled. Is this just simply a sign of chastity? Why have women’s bodies become so sensitive in traditional Iranian culture and why does the Islamic Republic of Iran lay so much emphasis on a strict requirement for the hijab?

As regards chastity, there are many references in Persian poetry showing that the hijab certainly does not contribute to a woman’s chastity. Perhaps the most famous story is that by Iraj Mirza (1874-1926) who offers an anecdote about a woman wearing a chador passing through an alleyway. The narrator stops her and begins a conversation with her. She is reticent as she is not allowed to talk to strange men. But the narrator’s eloquence convinces her to go to the man’s house. Here they have sex while she holds her veil tightly to her, not allowing the man to see her face and hair. The poet draws the conclusion that wearing a veil is certainly not a sign of chastity; but a woman who wears décolleté and is educated is chaste and virtuous. Iraj Mirza emphasises that chastity and religiosity have nothing to do with the veil but come with education and enlightenment. He sternly condemns the clerical hierarchy who set rules requiring the hijab.

Around the same period at the beginning of the twentieth century, another influential intellectual, Muḥammad-Riżā Mīrzāda ʿIshqī (killed in 1923), writes a splendid opera entitled The Black Shroud, comparing the veil to a shroud, implying that Iranian women are dead as long as they are imprisoned in such attire. He concludes that “so long as women are covered by shrouds, half of the nation is dead.” Also several Iranian female intellectuals such as Zhāla Qāʾim-Maqāmī (1883-1946) voiced their disapproval of the wearing of the mandatory veil, comparing it to black tar, sticking to women’s body and suffocating her.

There are endless examples in which the hijab is condemned. It is certainly sad to see that after a hundred years Iranian women are still struggling and are even being killed over a piece of cloth. When Riżā Shah (r. 1925-1941) issued the decree removing the veil in 1936, the situation gradually changed and women received more freedom and participated in society, establishing associations and organisations to advance their rights and positions. Riżā Shah’s son, Muḥammad Riżā Shah (r. 1941-1979), introduced women’s suffrage in 1963, a big step towards bestowing on women the rights they had long deserved. The responses of the clerical hierarchy, and of Khomeini (1902-1989) in particular, were fierce. The angry cleric sent a letter to the Shah, asking him to annul such an un-Islamic decision. Removing the veil and women’s participation in society were seen as a Western cultural invasion, which would damage Islam. Khomeini stirred up traditional Islamic and nationalistic sentiments among people, emphasising the irreconcilability of the western notion of womanhood with Iranian culture. It was in this period that Khomeini was arrested and later exiled to Turkey and then to Iraq. When he returned to Iran after the 1979-Revolution, the mandatory hijab also returned. This was the first step in curtailing the hijab and the rights of women.

Many people in Iran aspire to and embrace democracy, but the theocratic ideology of the Islamic Republic is opposed to such aspirations. According to a survey of Iranians’ attitudes towards different social and political topics (Gamaan – The Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in IRAN), a large percentage of the Iranian population is against the current Islamic Republic and religious injunctions. The question is for how long will the Islamic Republic hold to its severe theocratic principles. Mahsa’s murder opens a new chapter in the contemporary history of the battle of Iranian women against systematic oppression, exclusion and discrimination. Just a few days ago, the Iranian President, Ibrahim Raisi, avoided giving an interview to the British-Iranian top journalist Christian Amanpour in New York by requiring her to wear a veil. She rightly rejected this, and the interview was cancelled. Raisi’s response illustrates not only the Iranian regime’s attitude towards women’s rights and position in society but also his readiness to violate human rights and freedom of speech. Iranian women have been courageously fighting for their rights for the last 43 years. The Islamic Republic sees the veil as a symbol of chastity to curb women’s rights and freedom. The violation of the strict rules of the hijab, the charge on which Mahsa Amini was arrested and killed, is a justified cause for protest against oppression, a poor economic situation, censorship and basic human rights.

Selected literature

Afary, Janet, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Milani, Farzaneh, Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1992.

Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar, #MeToo in Persian poetry – Leiden Medievalists Blog

Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar, (ed.) Literature of the Early Twentieth Century: From the Constitutional Period to Reza Shah, London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Seyed-Gohrab, Asghar, Mirror of Dew: The Poetry of Ālam-Tāj Zhāle Qā’em-Maqāmi, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ILEX Foundation Series, 2014.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2022. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.