چادر پوسیده بنیاد مسلمانی نبود

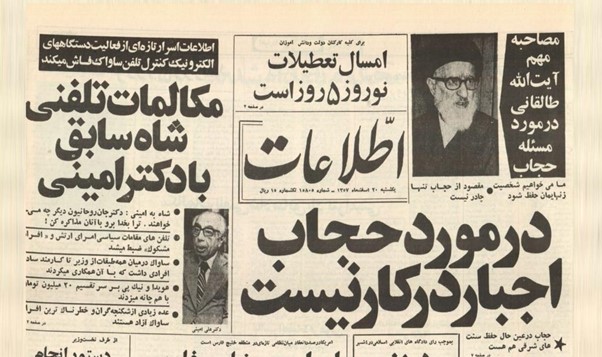

Women’s bodies have been used to project the ideology of ruling systems in Iran. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, controlling women’s bodies took a sharp Islamic turn. Soon women were forced to observe ḥijāb or the Islamic dress code or stay home to preserve morality in the Islamic society.

Women, along with men, in Iran have experienced oppressive patriarchal gender norms, promoted as Islamic codes of conduct. These codes of conduct, which are reinforced as laws, target men and women’s bodies as objects to be controlled. The question of Islamic ḥijāb for women has a long history in Iran. Today, the compulsory ḥijāb has turned into a sickle in the hands of the so-called ‘morality police’ claiming lives of Iranians, women and men. The brutality and violence in response to waves of repressed anger, recessing only to rise higher, has not stopped women from claiming the basic right of having control over their bodies. This piece serves as a brief backdrop to the issue of controlling women’s bodies in the contemporary history of Iran. I refer to a poem by Parvīn Iᶜtiṣāmī (1907-1941), a female author, who was engaged in the socio-political issues of her times. Her critical thoughts about the question of ḥijāb in Iran is an example of women’s frustration of being controlled in the name of religiosity.

The history of controlling women’s bodies in contemporary Iran starts with the Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911), which was an intellectual movement heralding progress and development in Iran inspired by early encounters with European countries. As one of the key elements in the movement, many Persian intellectuals pinpointed the problematic differences between Persia and Europe as the Persian women’s coveredness, seen as a sign of backwardness of the country. Women needed to become modernised to push the country towards progress. Consequently, the question of women’s veiling provoked heated discussions and controversies among intellectuals. Modernisers criticised the wearing of traditional veils or the chādur (‘the overall cover used by, mostly Muslim, women in Iran’), which they directly associated with gender segregation and the ‘backwardness’ of Muslim nations.Some writers suggested a link between traditions of female veiling and sexual issues such as paedophilia and homosexuality among Persian men. The controversial work ᶜĀrifnāma, a long mas̱navī (‘rhyming couplets’) composed by the poet Īraj Mīrzā (d. 1926) is one of these examples. In this poem, Īraj Mīrzā used biting satire to blame ḥijāb (which literally means ‘barrier’, and serves as the symbol of strict gender segregation) as the reason for sexual issues in Persian society. Although women’s veil was a fundamental question in the Constitutional Revolution, it was only under Riżā Shah Pahlavī (r. 1925-1941) that it turned into a dress code imposed by the government.

After the successful coup d’état in 1921 leading to the establishment of Riżā Shah Pahlavī’s monarchy in 1925, patriarchal disciplinary practices, such as women’s dress code, were introduced. According to these reforms, women were unveiled in 1936, as a step towards what was called ‘women’s emancipation’ and the ‘modernisation’ of Iran. Women were compelled to unveil if they wished to appear in public spaces and be active in society. Law enforcement agencies were directed to tear the traditional veils, or chādurs from women’s heads in the streets of Tehran and other major cities. This unveiling of women became a royal decree on January 7, 1936, and it was considered so important that this date came to be celebrated as Women’s Day, or women’s liberation day. In reality, however, this ‘modernising’ gesture resulted in a more severe violation of women’s rights as citizens. It deprived them of their control over their bodies and endangered their previously gained presence and agency in public and social spaces.

Parvīn Iᶜtiṣāmī (1907-1941), the progressive, Muslim female poet who experienced both the transformative period after the Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911) and the compulsory unveiling of women under Riżā Shah, wrote about the misery of women and ḥijāb in her long poem, Zan dar Iran (‘Women in Iran’). In the first couplet quoted and translated here, by using the metaphors of ‘desert of calamity and pit of affliction’ for ‘imitation’, she urges women to use their knowledge, to think rationally, and have control over their lives. In the second couplet, Parvīn asserts that women’s veiling is not an indicator of being a Muslim. Referring to chādur as worn-out, she calls for a mystical perspective about piety. Parvīn asserts that the veil is not the foundation of being a Muslim. The outward veil as prescribed by Islam would cover the body. For Parvīn, however, the term ‘veil’ has the mystical quality of being inward. The veil that Parvīn introduces to the world of womanhood is the virtue of chastity that would veil the eye and the heart:

بهر زن تقلید تیه فتنه و چاه بلاست

زیرک آن زن کو رهش این راه ظلمانی نبود

For women, imitation is a desert of calamity and pit of affliction.

shrewd is the woman whose path would not be this dark path.

چشم و دل را پرده میبایست اما از عفاف

چادر پوسیده بنیاد مسلمانی نبود

The eyes and heart should have veils, but out of chastity;

a worn-out veil would not be the foundation of being a Muslim.

For many Iranian women, as Parvīn expresses in her poem, ḥijāb has never been the sole symbol of piety or even religiosity. In the contemporary history of Iran, women’s bodies have changed into a tool to control and suppress not only the women, but the whole society. However, the extremely courageous movement happening in Iran at the moment is hopefully a harbinger of times when veiling or unveiling is women’s ‘own’ choice.

Selected literature:

Afary, Janet. Sexual Politics in Modern Iran. New York, Cambridge University Press: 2009.

Iᶜtiṣāmī, Parvīn. Dīvān. Edited by Heshmat Moayyad. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Special Persian Language Publications, 1987.

Milani, Farzaneh. Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women. New York, Syracuse University Press: 1992.

Najmabadi, Afsaneh. Women with Mustaches and Men Without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Sprachman, Paul. Suppressed Persian: An Anthology of Forbidden Literature. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publishers, 1995.

© Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2022. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.