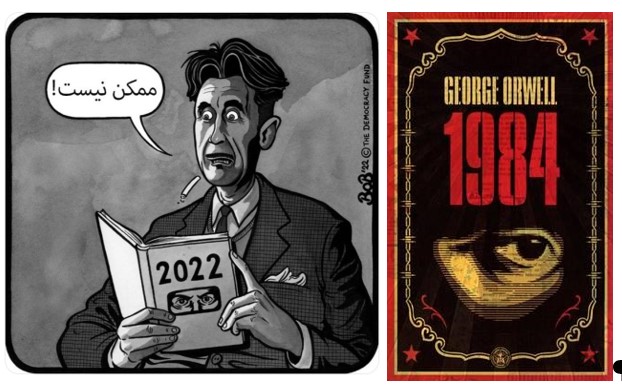

Many Iranians inside and outside their home country have compared the political situation in Iran after the Revolution of 1979 to the totalitarian and tyrannical state in George Orwell’s (d. 1950) dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Especially today, Iranians on social media express their grievances regarding the indescribable harsh repression of the ongoing protests by referring to Orwell’s book. What strikes me the most when reading Orwell is the way he describes how totalitarian regimes use language and literature in order to instil the state’s ideology on the masses, and transform any subversive concept or idea found in literature into a one-dimensional fabric of state ideology.

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

Orwell’s book, presumably inspired by Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany, focusses on themes such as totalitarianism, mass surveillance, class disparity, and the repression of citizens by the state. In the book, Big Brother is constantly watching, the nation is in a continuous state of war against foreign enemies as to create a general sentiment of fear and hate, and every day the past is rewritten by the Ministry of Truth (in addition to the Ministry of Peace which concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Love with torture and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the state attempts to warp people’s perception of reality by distorting their knowledge of the past and transforming language and literature into something that can merely express support for the official ideology of the state.

These attempts go to the point of absurdity when people are tortured in order to believe that the equation ‘two plus two’ makes five instead of four. Such attempts emphasise the lack of freedom of thought, and the distortion of objective facts such as this simple equation. This is reminiscent of the ways the Iranian regime has attempted to distort people’s perception of reality through language, especially by utilizing the richness and popularity of the classical Persian literary tradition.

During a conversation in Orwell’s book the protagonist Winston Smith and one of his colleagues at the Ministry of Truth, the philologist Syme, talk about the eleventh edition of the dictionary of “Newspeak” that replaced “Oldspeak” (the language before the revolution). Syme, who works on the new dictionary, explains the aims of the state by developing a new language.

Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten. […] But the process will still be continuing long after you and I are dead. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller.

Thoughtcrime here refers to the development of an individual’s ideas regarded by the state as possibly subversive. It points to the aim of the state to control the everyday lives of its citizens to the point of absurdity, to the point of the control of the mind. Under the totalitarian regime of Orwell’s book, the mind becomes the last frontier of rebellion which the state desires to break down by creating an immense structure of alternative facts and lies that are constructed by the Ministry of Truth on a daily basis. However, the individual that rejects these lies, and underlines the fundamental, unchangeable fact that the equation ‘two plus two equals four’ by openly stating it, retains the ability to think for her/himself. In this way, she/he remains in the possession of the key to the last bastion of that which we call “freedom”.

Politics, Religion, and Poetry in Post-Revolutionary Iran

In Iran, classical Persian poetry from the medieval period is still omnipresent in newspapers, books, journals, television, radio, art, architecture, and day to day speech. The verses of poets such as Sanāʾi (d. 1131), ʿAṭṭār (d. 1221), Rūmī (d. 1273), Saʿdī (d. 1291), and Hāfiẓ (d. 1390) are part and parcel of the everyday lives of the general population, and used by Iranians from all walks of life to express personal feelings and comment on social and political events. These poets belong to an antinomian tradition that is characterized by a wealth of non-conformist and transgressive ideas. These poets questioned common Islamic beliefs and practices during the medieval period. In their antinomian poetry, they mock formal religious practices such as praying, fasting, and frequenting the mosque in order to criticize outward forms of piety, merely fulfilling ones religious duties, and the hypocrisy of religious authorities.

Since the Revolution of 1979, the Iranian government has used the symbolic and social capital of classical Persian poetry in order to legitimize political decisions and monopolize conceptions of truth(s). An example is the way the Iranian government has used classical poetry to mobilize the masses to the front during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) and create a narrative in which the act of dying for the nation-state was celebrated. By utilizing a variety of mystical themes and motifs from the classical tradition, the government tried to contextualize the death of Iranian soldiers by linking it to the concept of martyrdom within the Islamic mystical tradition, in which martyrdom is imagined as ‘dying for God or the Divine Beloved’. In combination with the martyrdom of the third Shi’ite Imam Ḥusayn in the year 680 at Karbalā, a narrative was constructed in which themes and motifs of the classical Persian tradition were completely altered as to support the call for war and the official ideology of the state.

This hijacking of classical Persian poetry belonging to the antinomian tradition did not end after the eight years of the devastating war with Iraq, but continues until today in various forms. One example is the way classical Poets of the antinomian tradition have been included in the textbooks of primary and high school students where a particular reading in line with state ideology and the official version of Islam is promoted. In this new reading, the non-conformist ideas and concepts present in the classical poetry are used to support a one-dimensional reading of Islam and the state’s ideology, something that could not be further away from the initial meaning(s) of the poems. This is similar to the way the totalitarian regime in Nineteen Eighty-Four is attempting to transform the possibly subversive ideas present in literature into state-ideology, which results in dramatic changes of the initial meanings of monumental literary works. As Syme continues his explanation to Winston regarding the goal of the development of “Newspeak”,

By 2050 – earlier, probably – all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron – they’ll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually changed into something contradictory of what they used to be.

Today’s use of classical poetry by Iranians to criticize the regime shows that the government’s efforts to transform subversive ideas and concepts into the vocabulary of state ideology remains unsuccessful. Despite the attempts of the post-Revolutionary government, non-conformist ideas have been ingrained in Persian language and literature through the classical poetry belonging to the antinomian tradition. I think that Orwell might help us to understand how in Iran language and literature are used in attempts to transform the minds of citizens, and the way the concept of freedom is inherently related to the possibility of expressing one’s personal worldview freely. Because, according to Orwell, and the many Iranians who quote him,

Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two makes four. If that is granted, all else follows.

Selected Literature

Bruijn, J.T.P. de. Persian Sufi Poetry: An Introduction to the Mystical Use of Classical Persian Poems. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1997.

Orwell, G. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin Books Ltd, 2008.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. Martyrdom, Mysticism and Dissent: The Poetry of the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021.

Shams, F. A Revolution in Rhyme: Poetic Co-option Under the Islamic Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

© Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2022. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project