In the preface of her fifteen-thousand-couplet poetry collection, the Īnjūʾīd princess, Jahān-Malik Khātūn (d. about 1393) excused herself for writing poetry. This blog juxtaposes her act of writing with the mediaeval Iranian-Muslim gender norms, and introduces her as a pioneer of women’s transgression in Persian classical literature.

This brief blog concerns an Īnjūʾīd princess, Jahān-Malik Khātūn (d. about 1393), as a mediaeval forebearer of Persian women who have transgressed Iranian-Muslim gender norms. The quote below, from the preface Jahān-Malik Khātūn wrote to her poetry collection, is the most appropriate way to explain the gender norms which she transgressed:

… but since Persian women are extremely rare in this craft, I , too, imagined pursuing poetry as a defect, and avoided it at all costs. But through following succession, it became clear that elite Persian and Arab women have been famous poets. (Dīvān 2020, 3)

In these lines, a few key elements stand out: Writing poetry for women was considered a ‘defect’, and few Persian women had ventured into this arena. We further read that she avoided the craft of poetry ‘at all cost’, and we know that she was a royal woman. This probably indicates that the ‘defect’ she is referring to implies disgrace to her social status. The last sentence that she uses to excuse herself for writing corroborates the implication of losing dignity, since she refers to ‘elite’ women who were famous poets. What does Jahān-Malik Khātūn mean by writing this, and excusing herself for writing? Why does she need to start her Dīvān with these words? Farzaneh Milani’s argument about the problem of women and authorship in the Persian literary tradition can explain the issues here.

Ideal women in the traditional Persian culture were those who complied with ‘silence and immobility’. As Milani asserts, the root of such a construct was the association of women’s bodies and gender with shame. This gender norm was expanded to include women’s voices. For women, having a voice was as shameful as revealing their bodies. (Milani 1992, 48, 53, 118). With her poetry, however, this mediaeval Persian princess, tells us she is challenging these limiting norms, although she will face discrimination. We see one such example in the following short poem:

Men ask for an explanation about her/his conditions

If someone is imprisoned in the chain of fate

This is me that if someone accidentally says my name

S/he will ask for forgiveness out of fear a thousand times[1]

Jahān-Malik Khātūn probably wrote this poem in the aftermath of one of the major incidents in her life, the assassination of her father in 1343. Her uncle avenged this assassination and became the ruler of Shiraz. In the power struggles that followed, her uncle was overthrown, and all male members of her family were killed in 1353. She was imprisoned for a while and after being released, she was exiled (Davis 2020, 49). Jahān-Malik Khātūn’s poems are not dated, but the content of this short poem probably refers to her imprisonment. If we consider the hegemony of the Iranian-Muslim gender norms in the context, we may see her gender as the reason for composing these lines, to express the otherness that she experienced in addition to being excluded as a prisoner.

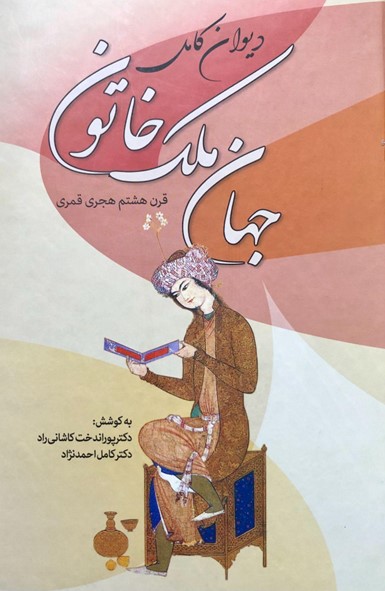

The Dīvān (“collection of poetry”) of this Īnjū’īd princess is the largest known volume of poetry composed by a woman to have survived to date (Brookshaw). She wrote about her personal life as a woman, and a mother. We can interpret several of her poems as accounts of her unhappy married life. She also wrote twenty-three elegies in which she lamented the loss of her young daughter (Davis 2020, 24). If we read the quote by Jahān-Malik Khātūn one more time, we can see the reason why she felt a need to justify her writing. Transgressing the patriarchal norms of her time, she used her voice to engage with a reading audience concerning many aspects of her life, although for a woman to take a public voice meant losing her dignity.

[1] My translation of the poem is literal to remain as close as possible to the original text. The literary translation of this poem by Davis is as follows:

When someone is imprisoned for a while

Men ask about his fate, and want to know his crimes

If someone accidentally says my name

Fear makes him beg to be excused, a thousand times

(Davis 2020, 58)

Works cited

Brookshaw, Dominic Parviz, in Encyclopædia Iranica, s.v. Jahān-Malik Khatūn.

Davis, Dick. The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women. Translated and introduced by Dick Davis, 1st edition. Washington D. C.: Mage Publishers, 2019.

Jahān-Malik Khātūn. Dīvān, edited by Pūrāndukht Kāshānī-rād and Kāmil Aḥmad-nizhād. First publ. 1374/1994-1995, Tehran: Intishārāt-i zavvār, 2nd repr., 1399/2019-2020.

Milani, Farzaneh. Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women. New York, Syracuse University Press: 1992.

© Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2023. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.