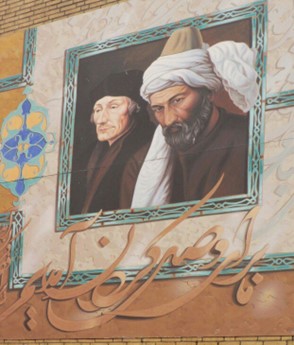

As a high school student I have biked numerous times through the Erasmusstraat in Rotterdam, but never did I pay much attention to the somewhat hidden mural painting at Erasmusstraat 137. The painting depicts Muslim philosopher, poet, and mystic Jalal al-Din Rūmī (d. 1273), and the Christian theologian, philosopher, and philologist Desiderius Erasmus (d. 1536). From the early modern period the city of Rotterdam claimed Erasmus as the city’s champion of humanism, and various schools, a university, and hospital bear the name Erasmus. Except for the famous Mevlana Mosque and several restaurants in Rotterdam, the veneration of Rūmī in the urban landscape of the city is recent. How did these two influential thinkers end up on a wall in the north of Rotterdam?

The anniversary of the 800th birthday of the Muslim philosopher, poet, and mystic Jalal al-Din Rūmī in 2007 led to the creation of the mural painting depicting ‘two humanists from east and west’ by the Iranian-Dutch artist Ahmad Haraji. In an interview in 2008, Caro van der Pluim from the Centre for Visual Arts in Rotterdam (CBK), who asked Haraji to create the painting, explains that “from a historic perspective, it is absurd to depict Mevlana Rūmī and Erasmus together.” However, according to Van der Pluim they both manifested a strong desire for religious tolerance. Therefore, the portrait of Rūmī and Erasmus “fits very well with Rotterdam’s desire for peaceful [social] integration.” The creation of the mural painting likely links to Rotterdam’s Turkish community and their high regard for Rūmī.

In the same interview, Haraji explains why Rūmī is so important for a city like Rotterdam.

“Rūmī said that love should be the basis for the world. He has the most peaceful interpretation of Islam. I think it is important that this side of Islam is also highlighted.” (Rietstra 2008)

This is also the reason why Haraji included a poem by Rūmī, underneath and on the left side of the mural paining in artisanal calligraphic form, which states:

We came to create a sense of union,

We did not come to generate division.

In this way, Rūmī and Erasmus are presented as two humanists from ‘east’ and ‘west’ who emphasise the importance of tolerance and union in Rotterdam’s multicultural society.

Rūmī’s Poetry on the Wall in Rotterdam?

However, while these verses sound very Rūmī-like, they are actually a variation of the following couplet:

Did you come to create a sense of union,

Or did you come to generate division?

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, II, 1755)

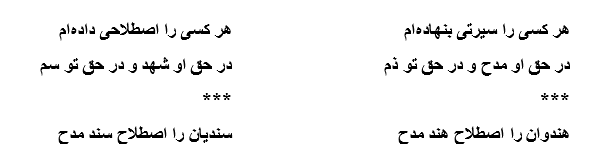

This is a couplet taken from Rūmī’s well-known story of Moses and the shepherd, one of the most popular stories from Rūmī’s Masnavī. Today, it is ubiquitous in anthologies, on ‘Rūmī-quote’ websites and transformed into several operas. In the story, Rūmī presents the prophet Moses as an orthodox theologian who rebukes a simple and illiterate shepherd for expressing his love for God in an anthropomorphic fashion. In the story, the shepherd asks, among other things, if he may “comb God’s hair” and “wash His clothes.”

Where are You, that I may become Your servant,

that I may sew Your shoes and comb Your hair?

That I may wash Your clothes and kill Your lice,

and bring Your milk to You, Your Eminence.

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, II, 1725-1726)

After Moses hears the prayer of the Shepherd, he reprimands the Shepherd for speaking to God in such a simplistic way, calls him a kāfar (“infidel”) and commands him to stuff some cotton in his mouth. However, God overhears Moses and rebukes him for having critiqued one of His loyal servants and worshippers. God underlines that He is not interested in outward forms of worship, or in how people express their devotion. As God explains to Moses,

From God a revelation came to Moses,

“You have repelled from us Our loyal servant!

Did you come to create a sense of union,

Or did you come to generate division?”

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, II, 1754-1755)

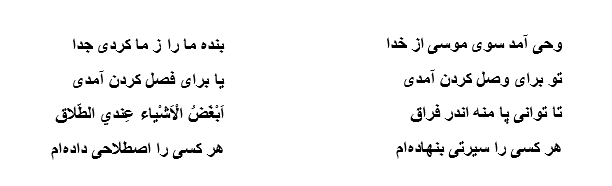

In his rebuke of Moses, God continues by explaining that everyone praises Him in a different way,

I have consigned a way for every one,

To everyone a different idiom.

For him it’s praise, for you disparagement,

for him it’s honey, and for you it’s poison.

***

For Hindis, Hindi is for praise of God;

the praise of God in Sindi is for Sindis.

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, II, 1757-58, 61)

After God’s rebuke, Moses realises that he made a mistake, and runs after the Shepherd to convey God’s message. However, when Moses finds the shepherd in the desert he realises that the man has undergone an inward, spiritual transformation; the shepherd has reached the highest stages of mystical insight and has become a ‘lover’ of God. And due to the sincerity of the shepherd’s love for God, he transcends the prophet Moses. While first Moses is convinced of the superiority of his own way of worshipping and reprimands the Shepherd for his blasphemous utterances, in the end he learns that sincerity is more important than the way someone expresses his or her devotion.

Mevlana Rūmī Roterodamus?

When we go back to the line of poetry on the wall in Rotterdam something interesting happened. While in the original story God asks Moses if he came as a prophet to unite people or create division, on the wall in Rotterdam is seems as if Rūmī and Erasmus express their clear message of tolerance: “we came to unite, not to separate.” The interplay between text and image creates a new story in which Rūmī and Erasmus are presented as two humanists from the ‘east’ and ‘west’, a story which perfectly fits in the municipality’s desire for “peaceful [social] integration.” In this way, two features are left out. First, it is forgotten that these words are actually God’s words. Second, Rūmī was inspired by medieval debates about Islamic piety, prophetology, and the relationship between man and God for the creation of the story of Moses and the Shepherd. While in the interview Haraji expresses his desire to show Rūmī’s “peaceful interpretation of Islam,” one wonders what is left of the Islamic context of Rūmī’s poem on the wall in Rotterdam.

Rūmī and Erasmus both undergo a curious transformation when viewed through a modern lens. Rūmī is often extracted from the Islamic tradition he belongs to and portrayed in a secular light that appeals to contemporary western audiences. Similarly, Erasmus is frequently portrayed as a secular thinker whose tolerant ideas stem purely from humanist principles, neglecting his Christian influences (Enenkel 2013, pp. 16-17). In addition, a deeper inquiry into the tolerance expressed by both figures is necessary. It becomes apparent that their conceptualization of tolerance often diverges from our present-day understanding, prompting us to question the nuances and complexities within their expressions of tolerance.

For many people, Rūmī’s story of Moses and the Shepherd offers a broad message of tolerance. In my reading of the story, I observe a clear critique of religious dogmatism that we also encounter in numerous other stories of Rūmī. But, in order to understand Rūmī’s poetry, including the story of Moses and the Shepherd, I think it is crucial to examine how such critiques of religious dogmatism have emerged from Rūmī’s discussions with Sufis, mystic poets, philosophers, and orthodox theologians. In other words, how did this story emerge from the Islamic medieval tradition? It is important to keep in mind that Rūmī’s verses have been central in the development of Sufi poetry, and Islamic thought in general. To redefine his place within the Islamic tradition, and the way his poetry deals with urgent theological questions during his life, changes our perception of Islam and Islamic history. It seems that especially today, in times of radical extremism and a growing repugnance for Islam in the West, we should pay greater attention to critiques of religious dogmatism expressed in Rūmī’s poetry, and how those ideas have shaped the development of Islamic thought. The mural painting on the wall in the north of Rotterdam is an inspiring artwork which enables us to think about such questions.

Cited Works

Enenkel, Karl A.E., “Introduction – Manifold Reader Responses: The Reception of Erasmus in Early Modern Europe,” pp. 1-24. In Karl A.E. Enenkel (ed.), The Reception of Erasmus in the Early Modern Period. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Rietstra, Thomas, “Dubbelportret Erasmus en Mevlana Rūmī,” Filosofie Magazine, 12 August 2008, https://www.filosofie.nl/dubbelportret-erasmus-en-mevlana-Rūmī/.

Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn, The Masnavī of Rūmī, Vol. II. Translated by Alan Williams. London: I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2020.

© Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2023. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.