Rūmī is often represented worldwide for his rich repertoire of love poetry. Social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook are permeated with ‘translated’ lines attributed to Rūmī on love. With a brief context, this blog juxtaposes love in the poetry of this Sufi Persian poet with its online representation.

Rūmī is mostly represented online for his poetry on love. The image above is an example from a Facebook account with a huge number of followers. The lines on the post, apparently translated from a poem by Rūmī, are about love and say: If you have much, give of your wealth. If you have little, give of your heart. What connotations of love does such a representation evoke in the minds of the readers on social media? What happens to Rūmī as a Sufi poet and his poetry when they are stripped from Islamic mysticism as their context? The Concubine and the King, a well-known mystic-didactic poem from Rūmī’s Mathnavi-yi maʿnavī (‘Spiritual Couplets’) can give the reader first-hand insight about love in this Sufi poet’s teachings.

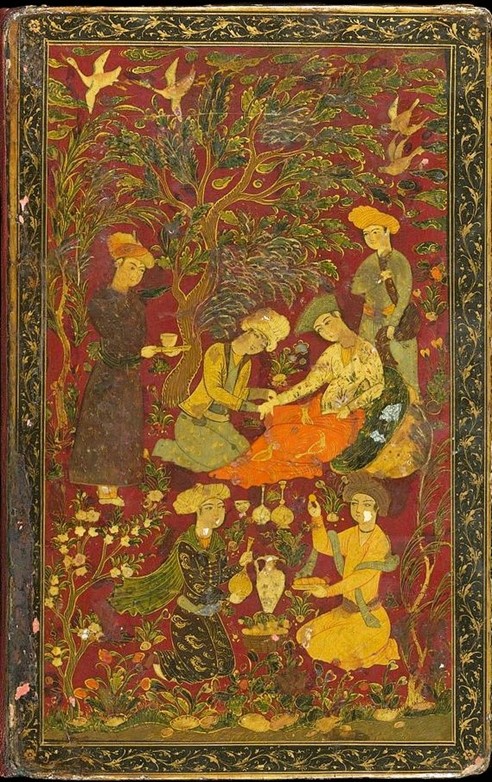

In this story, a king, an enslaved girl, a jeweller, and a divine physician are the main characters. One day, the king sees an enslaved girl, and falls in love with her (Rūmī 2007, 2-7). After buying her and enjoying union with her, she becomes very ill:

When he bought her and enjoyed union with her

it so happened that the enslaved girl became sick.

No physician can cure her. Desperate, the king implores God to help him and God sends him a divine physician. This physician uses the method of diagnosis that the Persian sage Avicenna used to diagnose the lovesickness of a royal figure (ʿArūẓī 1951, 121; Ibn Sīnā 1984, 287-311). He takes the pulse of the girl and asks her questions. Legend has it, when he utters the name of a specific neighbourhood in Samarkand, the girl’s pulse becomes faster. This way, he diagnoses her lovesickness for a jeweller from Samarqand, a city in present-day Uzbekistan.

The physician orders her union with this beloved, who is coaxed to come to the court of the king and live with her. When she recovers, the physician uses a special syrup and kills the jeweller; the girl’s love for her dearly cherished beloved fades away.

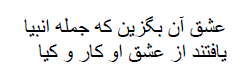

Rūmī concludes the story with his mystic-didactic message:

Choose love of Him from Whom the prophets all

derived their power and glory from His love.

(Trans. Williams 2020)

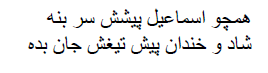

In the conclusion of the story, Rūmī refers to two Qurānic stories of Abraham sacrificing his only child, Ismāʿil, and the story of Khizr, accompanied by Moses (The Qurᵓān 37: 101-111; 18:71-82). This character, Khizr, is reported to have done three uncommon, and seemingly irrational deeds about which Moses kept questioning him. Rūmī refers to two of these incidents and justifies them; as the prophets obeyed God’s commands, and not their own whims. By comparing the story of the king, and prophets, Rūmī justifies poisoning and killing the jeweller because the physician committed it by God’s command. The way Rūmī concludes the story remains puzzling for many readers.

In Rūmī’s mystical teachings, love has two sides. It is the supreme force in the universe, bringing all entities of the universe into oneness. Love is also a purgatory process, turning the lover and the beloved into Love, through pain, suffering and anguish. It is a territory of sacrifice, and submission to the divine Will, as this line tells:

Lay down your head like Ismāʿil before Him

and laughing gaily, give His sword your soul.

In this story, Rūmī depicts the purgatory function of love and interprets God’s wrathful attributes as love.

This blog is a modified version of my Pecha Kucha presentation at the Rūmī symposium at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), 20 December.

© Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2024. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Zhinia Noorian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.

Sources Consulted

Furūzānfar, Badīʿ al-Zamān. Sharh-i masthnavi-yi sharīf: juzv-i nukhusīn az daftar-i avval. Tehran: Tehran university Press, 1969.

Ibn Sīnā, al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allāh. Qānūn: jild-i yak. Translated by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Sharafkandī. Tehran: Surūsh, 1984.

Nizāmī ʿArūẓī Samarqandī, Aḥmad ibn ʿUmar, Chahār maqāla. Edited by Muḥammad Qazvīnī. Leiden: Brill, 1910. Reprinted with notes by Muḥammad Muʿīn, Tehran: Intishārāt-i armaghān, 1331.

Noorian, Zhinia. “Van aardse liefde naar Goddelijke Liefde, De concubine en de koning”. Translated into Dutch by Maarten Holtzapffel, ZemZem. 2/2023. URL: 2023/2 Rumi – ZemZem (zemzemtijdschrift.nl)

Reuven Firestone, ‘Abraham’ in Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, ed. J.D. McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, 2001-2006.

Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad. The Masnavi of Rūmī Book 1: A New English Translation with Persian Text and Explanatory Notes. Translated by Alan Williams. London, United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris ; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad. Mas̱navī-yi maʿnavī, ed. Jalāl al-Dīn Humāʾī with a Persian and English Introduction by Mahdī Muḥaqqiq. Tehran: Muʾasisa-yi muṭāliʿāt-i islāmī-yi dānishgāh-i Tehran-dānishgāh-i makgīl, 2007.