(First published on Utrecht Religie Forum on March 24 2024)

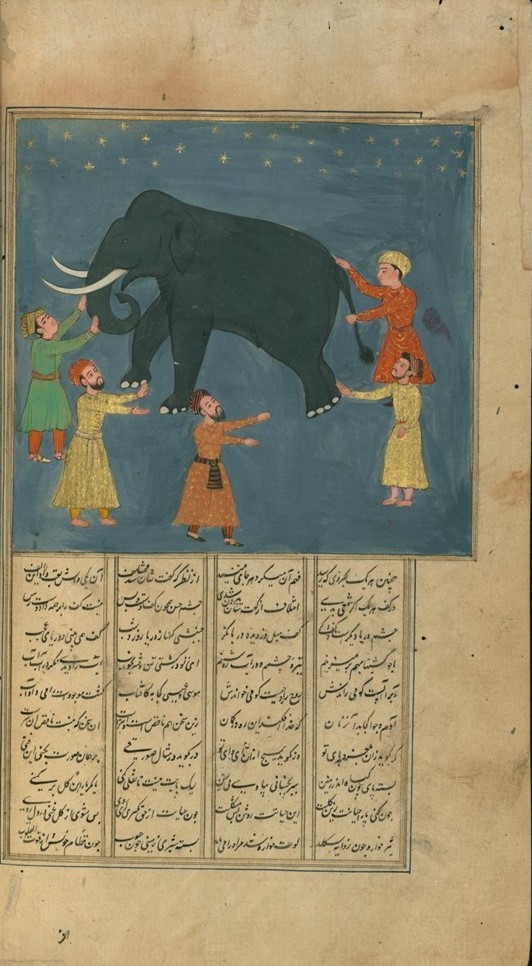

In this blog post, I explore one of the important questions that the Persian mystic-poet Jalal al-Din Rumi (d.1273) addressed in his writings. That question is the inquiry into the possibilities of arriving at the realm of the higher Truth. What does the Truth mean? How did Rumi ponder and discuss the potentials to attain elevated levels of truth and express them through writing? One example in which Rumi deals with this question is the well-known poem “Disagreeing about the essence and shape of the elephant”.

Modern interpretations, even though mostly tailored for a specific professional setting, show how adaptable the elephant parable can be in many different areas. For example, if you want to see how Rumi’s parable is applied in the field of education, you can click on this link.

Mistaking the elephant for a throne?

In Rumi’s poem, a group of individuals are in a dark house, struggling to discern what is right in front of them. Due to the absence of light, they are unable to recognize what is before them. Therefore, they misinterpret the elephant as different objects such as a fan, pillar, or throne depending on the particular area they touch.

| پیل اندر خانهٔ تاریک بود | عرضه را آورده بودندش هنود |

| از برای دیدنش مردم بسی | اندر آن ظلمت همیشد هر کسی |

| دیدنش با چشم چون ممکن نبود | اندر آن تاریکیش کف میبسود |

| آن یکی را کف به خرطوم اوفتاد | گفت همچون ناودانست این نهاد |

| آن یکی را دست بر گوشش رسید | آن برو چون بادبیزن شد پدید |

| آن یکی را کف چو بر پایش بسود | گفت شکل پیل دیدم چون عمود |

| آن یکی بر پشت او بنهاد دست | گفت خود این پیل چون تختی بدست |

| همچنین هر یک به جزوی که رسید | فهم آن میکرد هر جا میشنید |

“An elephant was brought to a dark building

By Indians, so they could hold a viewing,

So lots of people would come just to see—

They rushed into the darkness eagerly.

It was impossible to see it there.

So people groped to feel it everywhere:

One man’s hand brushed its trunk—he said, ‘This creature

is like a pipe.’ He based this on one feature.

Another could feel just its ears—that man

believed the elephant was like a fan.

Another felt one of its legs alone:

‘Its shape is like those columns made of stone.’

Another touched its back and then cried out:

‘It’s similar to a throne without a doubt.’

When they heard ‘elephant’ each one conceived

only the part that they themselves perceived.”

(Translation by Jawid Mojaddedi, p. 78, 2013)

Originating from ancient India, the earliest version of this parable was the legend of the elephant and the blind men. This legend was found in the Pali “Udāna” as part of Tittha Sutta, a Buddhist text. It has traveled vastly across various religions and lands.

In the cultural world of Islam, Rumi was not the first thinker who adopted this allegory. The 13th-century Sufi context that Rumi inherited had already appropriated the elephant parable to offer explanations for various religious and metaphysical questions. For instance, what constitutes the Truth? How can one discover it? What does this elephant parable tell us about the means of attaining knowledge in general and of spiritual knowledge in particular?

In a way, the elephant parable becomes an emblem of Truth-finding in Persian intellectual culture. Exploiting the elephant analogy, Rumi probes the limits of human tools for understanding the All-encompassing reality. The poet delves into the human perception system, encompassing both the intellect and the senses. In doing so, Rumi broadens the conversation to encompass the question of validity of various types of knowledge acquired by material means.

The Sensual Eye

Rumi appropriated the legend of the blind men and the elephant to comment on the failure of human perception to attain higher levels of mystical knowledge. From the imagery of the elephant in the dark house, Rumi moves to the metaphoric image of the foam and sea to further elaborate on the topological relationship between human sensory faculties and the Truth of existence.

| نیست کف را بر همهٔ او دسترس | چشم حس همچون کف دستست و بس |

| کف بهل وز دیدهٔ دریا نگر | چشم دریا دیگرست و کف دگر |

“The sensual eye’s no better than the hand—

The whole of it the hand can’t understand.

The ocean’s eye and foam are worlds apart—

Leave its foam, use the eye inside its heart!”

(Translation by Jawid Mojaddedi, p. 79)

Rumi asserts the dichotomy of the sensual eye and the ocean’s eye to distinguish between different manners of perceiving the world. In his view, the sensual eye is defective as it is limited by corporeality and the boundaries of the material world.

In Rumi’s philosophy, the world that we perceive through our senses and intellectual faculty is similar to the foam of the sea. As the foam covers the depth of the sea from sight, the worldly forms perceived by sensory perception are illusory and veil the Truth of existence.

The Practice of Truth-writing

To find the Truth it is important to switch off rationality and transform sensory perception from lower senses to higher spiritual senses. The human intellect is limited as humans are only a part of the whole. Therefore, they can never understand the whole of the Truth, just like the elephant. As the wisdom of the heart cannot be transferred through words and is unattainable by material means, Rumi ends up criticizing the body of his own poetry. He further emphasizes the inability of material means to attain authentic esoteric knowledge.

“This discourse falls short still, and is deficient;

The Speech of God alone can be sufficient.”

(Translation by Jawid Mojaddedi, p.79)

This English blog is a modified version of my presentation at Rumi symposium at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), 20 December 2023. A longer Dutch version of this piece is published in the special issue of ZemZem: tijdschrift over het Midden-Oosten, Noord-Afrika en islam (2/2023) devoted to the Persian poet Jalal al-Din Rumi.

Furūzānfar, Badīʿ-al-Zamān, Aḥādīth va qiṣaṣ-i mathnavī, ed., Ḥusein Dāvūdī Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1381/2003.

Meier, Fritz ,“The Problem of Nature in the Esoteric Monism of Islam”, in Spirit and Nature Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks, ed. Joseph Campbell. New York: Pantheon Books.

Rūmī, Jalāl-al-Dīn Muḥammad, Mathnavī-yi Ma ʿnavī, Vol. 3, ed. Reynold A. Nicholson. Brill: Leiden, 1929.

Rūmī, Jalāl-al-Dīn, The Masnavi (Book Three), trans. Jawid Mojaddedi, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

© Fatemeh Naghshvarian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2024. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Fatemeh Naghshvarian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.