Persian narrative poetry (mathnavīs) is mostly known for its monumental lovers. The names of Vīs and Rāmīn, Leylī and Majnūn, Shīrīn and Khusrow, are familiar to the ears of Persian readers and their stories are well-known. The heroic journey of the lover-protagonists, who go through various adventures and traverse dangerous paths to explore the uncharted territories of the convoluted concept of love is an integral part of Persianate sensibilities. It is in the romantic epic that lovers become the focus of the story and love becomes a central theme through whose lens a set of values, beliefs and aesthetics are established.

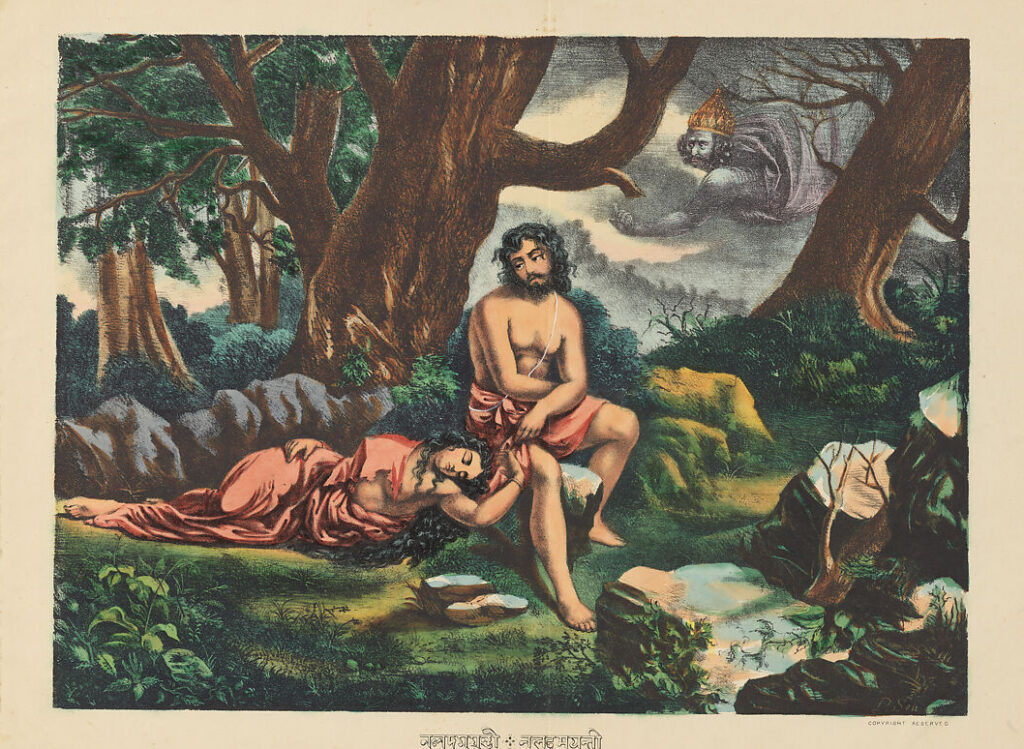

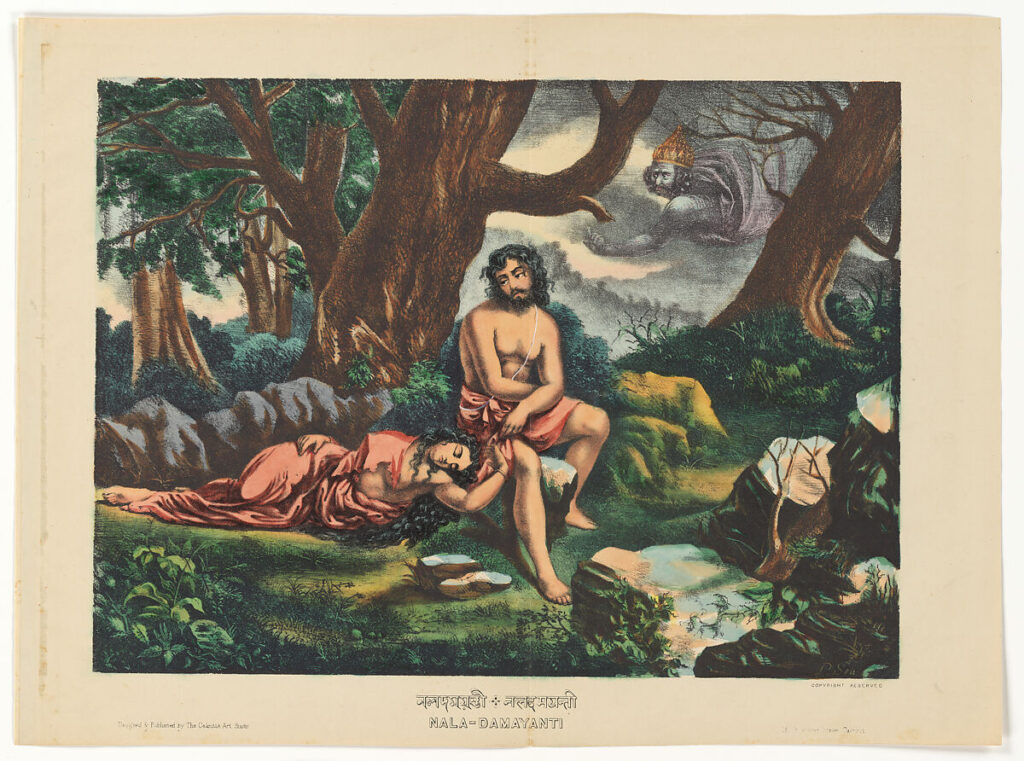

In this blog, I will look at the character of Nal from the story of Nal-u Daman by the Persian-speaking Indian poet Feyżī Fayyāżī (d.1595). This romance is derived from a segment of the Sanskrit Mahabhārāta and is a response to the popular romance of Leylī-u Majnūn by Niẓāmī Ganjavī (d.1209). Like Niẓāmī’s Majnūn, King Nal’s troubles start with his growing lovesickness (sowdā). Love disrupts the course of Nal’s life and ultimately transforms him into a dervish. Among the similarities between Nal and Majnūn, I will concentrate on how their outward appearances mirror their internal changes.

Similar to Leylī-u Majnūn, Nal-u Daman is rich in mystical expressions and spiritual themes. Drawing on popular stories familiar to their audiences, Niẓāmī and Feyżī exploit Arabic and Hindu literary imagination, respectively, to depict characters overwhelmed by love to the point of societal transgression. Both poems intertwine earthly and spiritual love, reflecting Sufi ideas of love. The lovers’ extreme devotion leads to an organic form of asceticism, as seen in their sleep deprivation and lack of clothing, paralleling each other’s appearances and experiences.

Estrangement, Exile and Mortification

The lover’s journey is similar to that of an ascetic. Like an ascetic, who denies himself food and sleep, the lover is unable to eat or sleep on account of separation from the beloved. The lover sees the image of the beloved everywhere and everything else loses its significance. The main point of diversion between a lover and an ascetic is that the ascetic’s actions are intentional, whereas the lover is driven by the force of love. This love causes the lover’s sleeplessness, mortification, constant meditation on the beloved, and finding satisfaction only in the beloved. Niẓāmī ‘s Majnūn embodies both the detachment of an ascetic and the overpowering force of love. Feyżī’s Nal follows the same trajectory. Nal’s transformation into a dervish depends on the force of love and the flux of madness.

In Nal-u Daman, overwhelmed by intense love, King Nal progresses from the conflict between love and intellect (ʿaql) to madness (junūn). He loses his kingdom in a gambling game and is exiled with his beloved Daman. Stripped of all his wealth and his good reputation, King Nal becomes alienated from society, left naked, hungry, and sleep-deprived, pondering the source of his suffering in the wild.

| ای صبح چرا نمیزنی دم | کاین تیره شبم بکشت از غم |

| وین مغز که سوخت در سر من | این دل که گداخت در بر من |

| دیوانگی مرا فسون کرد | بیخوابی این شبم زبون کرد |

| وین خاک که کرد بر سر من | این فال که زد به اختر من |

Since dark night has killed me with sorrow,

O dawn, why do you not respire?

Who has melted this heart in my chest?

And who has burned this brain in my head?

Tonight again, the sleeplessness has made me weak,

Madness has put a spell upon me,

Who has struck this omen to my star?

And who has thrown dust upon my head,

King Nal’s misfortunes extend beyond losing his kingdom and all of his material possessions. During his exile, he attempts to persuade his beloved Daman to leave him and return to her parents’ palace. Although Daman refuses and chooses to remain by his side, he is unable to bear the sight of his wife in such a state. Nal decides to leave Daman alone in the night as she is asleep. Feyżī presents the audience with Nal’s internal dialogue:

| از طالع من سیاه روزست | کاین گل که چراغ دلفروزست |

| (…) | |

| چون بنگرمش به خار و خاره | پایی که ببوسدش ستاره |

This rose, which is a heart-illuminating lamp,

has a black day because of my ill-star.

(…)

A foot that is kissed by a star.

How can I look at it, as it is full of thorns and thistles?

In both Leylī-u Majnūn and Nal-u Daman, the protagonists’ intense love leads them through a transformative journey marked by estrangement, and self-mortification.

Metamorphosis

In Leylī-u Majnūn, Majnūn is described as having an emaciated, bare, and wounded body. In addition to his ascetic-like physical appearance, he rigorously follows ascetic practices such as celibacy, self-mortification, avoidance of sleep and food, and seclusion. Like Nal, Majnūn becomes estranged from society and is mocked. Driven by the intensity of his love and the pain of separation, he seeks refuge in nature and earns the title of King of animals and plants.

In the same vein, Nal, after losing his beloved, goes to the mountains and lives among animals while suffering from the pain of separation. One day, he rescues a snake engulfed in flames, which bites him and turns him black. The snake assures Nal that the blackness is a temporary disguise and will be useful when the time is right. The snake promises to remove the blackness when fortune comes Nal’s way. The snake gives Nal a piece of its skin to keep, which he can use to summon the snake when needed. The snake explains the qualities of his black appearance:

| کافور تو مشت شد چه باک ست | دانم که دل تو بیمناک ست |

| باید که دلت سیه نباشد | در تن سیهی گنه نباشد |

| وز کرده خویش برنگردم | از حکم قضاست هرچه کردم |

| از وی همه ناتوانی و زور | سر بر خط اوست مار تا مور |

| مشکاف که سر به مهر رازی ست | هرجا که نشیب یا فرازی ست |

| مخروش که خال رو سفیدی ست | از رنگ سیه چه ناامیدی ست |

| بس رشته فکر را سراست این | بس حکمت ژرف را دراست این |

| در جوی مراد آرد آبت | این شاهد عنبرین نقابت |

I know that your heart is fearful.

Your camphor was crushed in the fist, do not be afraid!

There is no sin in having a black body.

Your heart should not be black.

For it is the decree of fate whatever I did.

And I won’t turn back from what I have done.

The head is aligned to His line, whether being a snake or an ant.

Weakness and strength come from Him.

Wherever there is an up and down,

do not open it, for a secret is hidden under a seal.

Why despair at blackness?

Do not cry, for the black beauty spot is a sign of honor!

Much profound wisdom is behind the door.

Many threads of thoughts are inside the head.

This amber-scented witness is your mask.

It will answer your wishes in the stream of desire.

According to the snake, Nal’s physical metamorphosis, embodied by the color black, should not cause despair, as it signifies hidden secrets and the complexity of fate. On account of its dark nature, black is introduced as a mark of beauty and honor and reflects profound wisdom.

Nal’s external changes symbolize his evolution as a character, occurring in two stages: initially, he loses his kingdom and even his beloved, followed by his physical metamorphosis. The snake contains various layers of meanings in Persian literature, representing the lower self (nafs), material world, and transformation. In the Sufi tradition, it represents the mystic’s journey of shedding ego and attaining divine enlightenment, as depicted in Nal’s encounter with the snake. After this encounter, Nal refers to himself as a dervish, reflecting an internal awakening to human dependence on God.

Similarly, in Leylī-u Majnūn, Majnūn’s external appearance, often compared to a snake, signals symbolic significance, reflecting Majnūn’s inner state of mind. Majnūn’s physical appearance changes throughout the poem, transitioning from the comparison of his infant’s face to the moon’s beauty to a dehumanized state resembling a snake. The physical transformation in the stories marks the psychological traits exhibited by lovers consumed by love. The lovers’ physical and mental sufferings highlight the transgressive impact of love, blending the deliberate detachment of an ascetic with the consuming power of passionate love.

Cited Works

Alam, Muzaffar and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. “Faizi’s Nal-u Daman and its long afterlife”. In Writing the Mughal World: Studies on Culture and Politics. New York: Columbia University Press,2012.

Bürgel, Johann Christoph and C. van Ruymbeke. A Key to the Treasure of the Hakīm: Artistic and Humanistic Aspects of Nizāmī Ganjavī’s Khamsa. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2011.

Feyżī Dakani. Nal va Daman. Edited by Seyed Ali Al-e Dāvūd. Tehran: Markaz-i Nashr-i Danishgāhī, 1382.

Nezami Ganjavi. Layli and Majnun. Translated from Persian by Dick Davis. New York : Penguin Books, 2021.

Seyed-Gohrab, Ali Asghar. Laylī and Majnūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Niẓāmī’s Epic Romance. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2003.

Talattof, Kamran. Nezami Ganjavi and Classical Persian Literature: Demystifying the Mystic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2022.

© Fatemeh Naghshvarian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2024. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Fatemeh Naghshvarian and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.