(This blog is an English translation of an earlier published article in Dutch at Utrecht Religie Forum)

Even those who do not know much about Islam are familiar with the fact that in most Islamic traditions the dog is considered unclean. There are, of course, exceptions, such as watchdogs, sheepdogs and hunting dogs, but the dog is not a companion animal. At least, that is the common idea in the West. In Sufism, the dog is a symbol of the baser self (nafs) but also represents humility. Mystical Islam treats dogs differently.

Islamic mystics, or Sufis, treat animals with respect. In many Sufi texts we encounter anecdotes, metaphors and allegories in which mystics show their compassion for animals. In this blog, I would like to refer to a few examples, showing how Persian mystics treat dogs. These mystics were probably influenced by pre-Islamic Persian culture, in which dogs were respected.

According to ancient Persian folk etymology, the word for dog sag is probably derived from seh-yak or “one third,” because one third of the animal’s essence would be human. In Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Persia, dogs were respected and had a role in rituals such as sag-dīd (“seen by the dog”), which required a dog to look at a corpse to ward off infection before the corpse was placed in its resting place, and to leave this world for the next. As Mahnaz Moazami quotes from Dēnkard, an encyclopedia of Zoroastrianism, “when a dog looks at the open face of a corpse, its gaze has the power to contain the demons of dead matter in the body and prevent them from escaping and infecting the living world.” It was believed that dogs had the power to chase away Nasu, a demon, the greatest polluter of the world of Good God, Ahura Mazda.

In a previous blog, I discussed a story in which Jesus sees a dead dog and praises its teeth, which shine like pearls. The pearl symbolizes the soul, which survives the body. A similar idea appears in the Conference of the Birds by the Persian mystic poet Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār (d. 1221), where the dog is also used to symbolize the soul. In this story, a king asks his servant to bring him his beloved dog. When the servant leads the dog on a leash, the animal stops to chew on a piece of bone instead of eagerly running towards the king. Displeased, the king orders the dog released to take care of itself. Meanwhile, however, the dog returns to the king and realizes that it really belongs to him. In this story, the dog represents the soul and the king symbolizes God. The dog’s distraction by a bone reflects the soul’s attachment to trivial worldly matters. As a result, God distances himself from the soul and allows the soul to experience life on its own. Yet the soul eventually understands its true purpose and destiny, i.e., return to the Divine. Through this story, ʿAṭṭār foregrounds a central theme of Sufism, namely the realization that the ultimate goal of life is the soul’s union with God.

Another anecdote highlighting the mystics’ respect for animals comes from the Persian poet Niẓāmī of Ganja (d. 1209). He tells a story about Rābiʿa al-ʿAdaviyya (d. 801), the first prominent female Islamic mystic. While traveling through a scorching desert, Rābiʿa saw a dog that was dying of thirst. Moved by this scene, she cut off her long hair, braided it into a rope and lowered it into a well to fetch water for the suffering animal. Rābiʿa’s kind treatment of animals is a recurring theme in her stories, especially since she was a vegetarian and had a close relationship with animals. Her actions reflect the Sufi ideals of compassion, humility and love for animals.

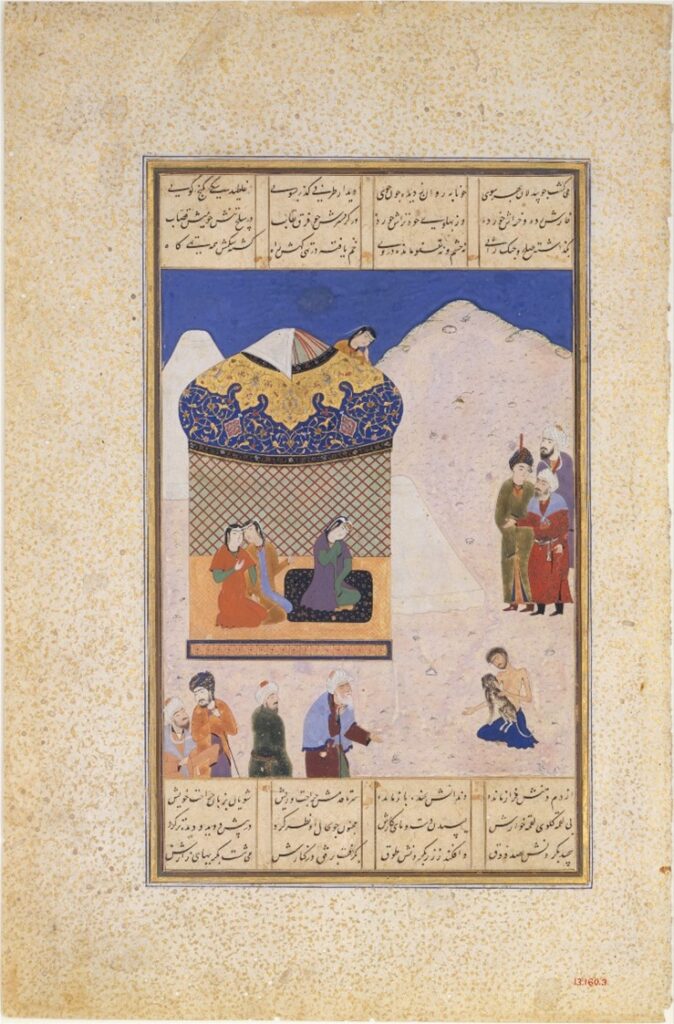

The dog has a fascinating and enduring place in Persian culture, rooted in ancient traditions, literature and mysticism. One of its iconic representations appears in the famous love story Leylī and Majnūn, which is a favourite romance throughout the Islamic world. In this story, the lover Majnūn finds solace by embracing a dog from Leylī’s alley. For him, the dog becomes a precious connection to his beloved; everything related to Leylī becomes sanctified and turns into a relic of devotion. In Persian paintings, Majnūn is sometimes depicted while embracing a dog lovingly, a gesture expressing his love and yearning. This image grew into a recurring motif in the Persian literary tradition.

These examples show how dogs played a prominent role in various domains of Persian culture including rituals, arts and literature, and religion and spirituality. In ancient Zoroastrianism, dogs were considered guardians of purity, reflecting the deep respect these animals enjoyed. This appreciation persisted during the Islamic period as well, particularly within Sufism. In Sufi philosophy, the dog symbolizes humility and devotion, prefiguring the human soul, longing for union with the Divine. The dog’s loyalty also resonates in Persian love stories, where it acts as a connecting bond between lovers. For Majnūn, the dog becomes a substitute for Leylī; its presence provides comfort and evokes memories of his unattainable love. This image illustrates the reverence for dogs in Persian culture, in which they are celebrated as symbols of purity, fidelity and spiritual longing.

ʿAṭṭār, Farīd al-Dīn, Manṭiq al-ṭeyr, ed. Sayyid Ṣādiq Gowharīn, Tehran: Shirkat intishārāt-i ʿilmī va farhangī, 1989.

Boyce, M., in Encyclopædia Iranica, s.v. Dog, 2. In Zoroastrianism.

Davis, D., “The Journey as Paradigm: Literal and Metaphorical Travel in ʿAṭṭār’s Mantiq at-tayr,” in Edebiyāt: The Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1993, pp. 173-83.

Moazami, M., Encyclopædia Iranica, s.v. Nasu.

Nezami Ganjavi. Layli and Majnun. Translated from Persian by Dick Davis. New York: Penguin Books, 2021.

Niẓāmī Ganjavi, Makhzan al-asrār, ed. W. Dastgirdī, Tehran: Armaghān, 1934, second edition, ʿIlmī, 1984.

Nūrbakhsh, J., Sag az dīdgāh-i Ṣūfīyān, London: Khāniqāh-i Ni’matullāhī, 1366/1987 (translation: Dogs from a Sufi Point of View, London: KNP, 1989).

Omidsalar, M. & T.P. Omidsalar, in EIr, s.v. Dog I.

Pourjavady, N., “Sag-i kū-yi dūst va khāk-i rāhash,” in Nashr-i Dānish, No. 3, 15, 1374/1995, pp. 9-15.

Ritter, H., The Ocean of the Soul: Man, the World and God in the Stones of Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār, Translated by John O’Kane with Editorial Assistance of Bernd Radtke, Leiden 2003 (translation of Das Meer der Seele: Mensch, Welt und Gott in den Geschichten des Fariduddin ʿAṭṭār, Leiden: Brill, 1955).

Schimmel, A., Mystical Dimensions of Islam, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1975.

Schimmel, A., The Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaloddin Rumi, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1978.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A., “Longing for Love: The Romance of Layla and Majnun,” in A Companion to World Literature, ed. Ken Seigneurie, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, Volume II, 601 to 1450, 2020, pp. 861-872.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A., Laylī and Majnūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Niẓāmī’s Epic Romance, Leiden / Boston: Brill, 2003.

Shafīʿī-Kadkanī, M.R., Qalandariyya dar tārīkh: digardīsīhā-yi yil īdiuluzhī, Tehran: Sukhan, 1386/2007. Viré, F., in Encyclopaedie of Islam, s.v. Kalb.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2025. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.