| For dancing in the street For being frightened when kissing For my sister, your sister, our sister For changing the brains that are worn out For the shame, for having no money For envying an ordinary life For the child who searches in dustbins and his hopes For this imposed economy For this polluted air For the Vali-Asr avenue and its worn out trees For Piruz and the possibility of its extinction For the innocent dogs that are forbidden For endless weeping For repeatedly visualising this moment For the face that is smiling For students, for the future For this imposed Paradise For the imprisoned bright minds For the Afghan children For all this, for all these unnamed ‘fors’ For all these empty slogans For the houses that are caving in For the feeling of calm For the sun after long nights For the pills for stress and insomnia For man, homeland, prosperity For the girl who wished to be a boy For woman, life, liberty For liberty For liberty For liberty | برای توی کوچه رقصیدن برای ترسیدن به وقت بوسیدن برای خواهرم خواهرت خواهرامون برای تغییر مغزها که پوسیدن برای شرمندگی برای بی پولی برای حسرت یک زندگی معمولی برای کودک زبالهگرد و آرزوهاش برای این اقتصاد دستوری برای این هوای آلوده برای ولیعصرو درختای فرسوده برای پیروزو احتمال انقراضش برای سگهای بیگناه ممنوعه برای گریههای بیوقفه برای تصویر تکرار این لحظه برای چهرهای که میخنده برای دانش آموزا برای آینده برای این بهشت اجباری برای نخبههای زندانی برای کودکان افغانی برای این همه برای غیر تکراری برای این همه شعارهای توخالی برای آوار خانههای پوشالی برای احساس آرامش برای خورشید پس از شبای طولانی برای قرصهای اعصاب و بیخوابی برای مرد، میهن، آبادی برای دختری که آرزو داشت پسر بود برای زن، زندگی، آزادی برای آزادی برای آزادی برای آزادی |

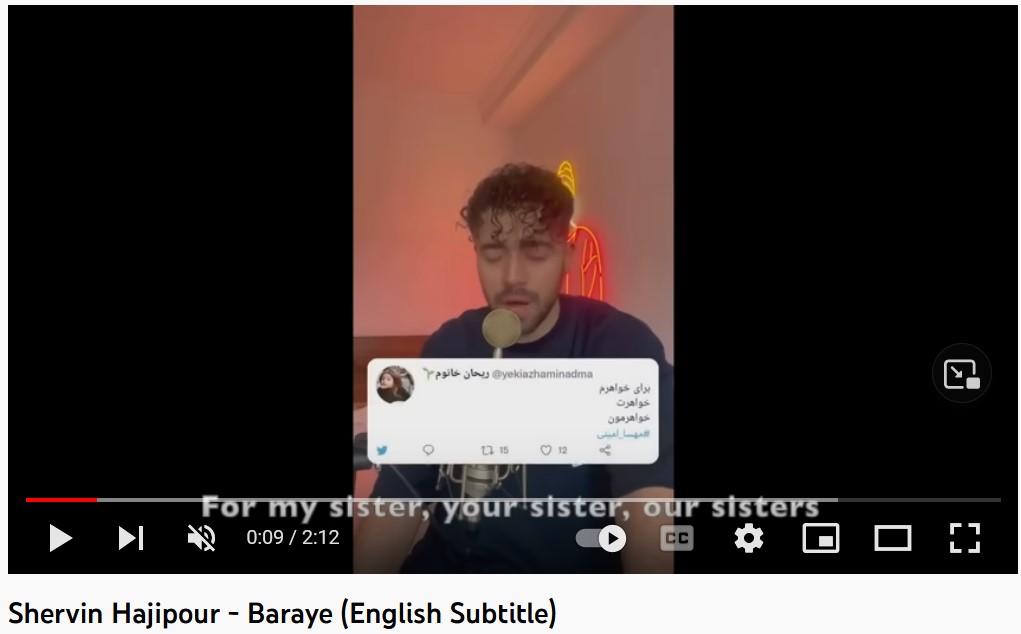

Shervin Hajipour’s Baraye

On 16 September 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini died, two days after having been arrested for showing a lock of hair. Since then protests have erupted all over Iran. During the demonstrations various Persian songs are sung. The most popular song of this time is without a doubt Shervin Hajipour’s, which went viral immediately after its release. Iranian celebrities such as Ali Karimi, the former Bayern Munich footballer, posted the song on their Instagram accounts to protest against the excessive violence, showing their support for Iranian women. Shervin himself was arrested on 29 September and the song was removed from his Instagram account, but it has since been shared millions of times on various social media. Schoolchildren and students sing it to express their disapproval of the Islamic Republic’s policy. The song is also used during demonstrations inside and outside Iran. The scale of the protests is enormous; the courage of the Iranian girls and boys is heroic; the violence with which the regime is responding to the call for freedom is unprecedented. Shervin’s lyrics have become the soundtrack of the recent protests, not only because of their form and content, but also because of Shervin’s performance. He sings every word, every syllable, intensely. His voice is trembling, it is as if he is crying. His eyes are closed and it is only at the end of the poem that we see them, at the moment when he alludes to “the pill for stress and insomnia.” From this moment on, he looks directly into the camera. His eyes are swollen as if he has been crying.

The Song

Each of the 31 phrases begins with the Persian word barāye, which means “for,” or “because of.” The word thus encompasses both “reason” and “beneficiary.” Every line has its origin in Iranians’ messages on social media. Together they form a catalogue of the problems the Iranians are facing, pointing to the oppressive situation after 43 years of Islamic rule. The problems are not new, but the artistic and coherent way in which Shervin has put them together has a huge emotional impact. People long for freedom and these sentences show how Iranians have been deprived of the most basic human rights.

The song shows what is at stake, what people have been deprived of, and the desire for change in the current ideological theocratic system. It is not just about the restrictive dress code and gender segregation, but also about poverty and environmental pollution, the consequences of the ubiquitous corruption, and years of mismanagement. Shervin’s song does not mention the dress code for which the 22-year-old Mahsa Amini was arrested and murdered by the morality police. He does mention the ban on dancing and kissing. Dancing and music have been problematic from the beginning of the 1979 Revolution. It is not surprising that girls dance when they remove and burn their headscarves. Both taking off the headscarf and dancing exemplify the desire to be able to express oneself freely.

Another important theme is poverty. While Iran as an oil-producing country is one of the richest in the region, very little of the profit ever reaches the population. Obviously, the sanctions imposed by the US and other Western countries play a role here, but the Islamic Republic spends the money, principally on its own people or on ideological objectives abroad, especially in countries such as Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. From time to time, Iranians come across news about how the state elites smuggle millions of dollars abroad and who let their children, shouting “death to America,” live a life of luxury in the West. The luxurious life of these children with their expensive sports cars, large villas and extravagant parties is in stark contrast to the poverty-stricken Iranian population struggling with astronomical inflation, poor infrastructure, unemployment and increasing water shortages. The contrast between what the Islamic Republic is doing and what it is demanding from the Iranian people has become too stark. Against this background, the longing for an “ordinary life” expressed in the song has tragic connotations.

The environment

Another theme Shervin brings up is the environment. Iran’s infrastructure has deteriorated in recent decades. Larger cities struggle with air pollution; there is mismanagement of water resources, partly related to the demographic growth from 35 million in 1979 to some 85 million now, strongly promoted by the Islamic Republic. All of these pose major problems to a country that is largely made up of deserts and mountain ranges. In the song the mention of Piruz is a reference to the extinction of species. Piruz is a leopard cub rescued by nature conservators when its mother was killed. The Persian (Asian) leopard is on the brink of extinction. The leopard is, incidentally, also the emblem of the Iranian national football team (tim-e melli). It is on their jerseys, symbolising their strength, persistence and speed. The reference to the worn-out trees being cut down on Vali-Asr avenue is to the poor environmental policy, evoking at the same time the nostalgic image of one of the longest and most beautiful streets in Tehran, which runs from the north of the city to the south. Despite all these problems, the Islamic Republic still encourages people to have more children. Children searching through dustbins for food is an all too common sight in Iranian cities.

The Greatest Wish

What the poem powerfully brings out is the wish for a life that for so many people, for example in the West, is a given. It does not seem to be too much to ask for, yet it feels like the greatest wish of all. The Islamic Republic adheres to the conviction that this material world is ephemeral, and, therefore, a Muslim should focus on the eternal world in the heavenly gardens. But Iranian people desire to live now, on earth. Some people say that the rules of the theocratic state are driving people to Paradise so strongly that they are falling into hell on the other side. For all these reasons and many more, the Iranian people are now protesting in the streets.

References:

Shervin Hajipour – Baraye (English Subtitle) – YouTube

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2022. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.