In this short blog, I examine the illustrations of Edward FitzGerald’s English adaptation of the Rubāʿīyāt by the well-known British artist Gilbert James (d. 1941). I show how his illustrations differed from his contemporaries and explain some of the art historical implications of this difference.

William H. Martin and Sandra Mason comment on the illustration Rubāʿīyāt that “by the end of 1909, there had been over 100 new illustrated or decorated editions of FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat, containing the work of over 50 different artists. Many of them were key figures in the art nouveau movement, including Edmund Dulac, Rene Bull, Robert Anning Bell and Jessie King” (see this entry in Iranica). But Gilbert James’ illustrations deviated from the norm in certain ways. They invite further analysis and reflection. Let me give you a snapshot of the debates that some of his works sparked at the time. In 1899, the editor of the British magazine The Idler, Arthur Lawrence publishes his interview with Gilbert James (see Bob Forrest’s blog post for more details on Gilbert James). Introducing the artist, Lawrence mentions that “on the one hand, one hears the profoundest admiration expressed for it, and on the other an utter repugnance thereto” (Lawrence, 581). In this same article, a few of these responses are given.

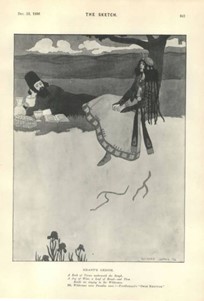

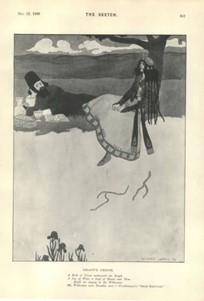

The first comes from a lady from London who writes to the editor of an illustrated magazine, The Sketch, asking for more of James’ art for her living room. In contrast to this friendly feedback, a doctor in Preston writes to the same editor about one of James’ recent works The Book of Esther, which was an illustrated version of a biblical story, “dear sir, I beg to offer you cheap my series of illustrations on Biblical subjects, and present you free with a sample, subject, ‘Eve tempted by the Serpent’” (583). The article also provides the doctor’s sketch (Figure 1).

And then he continues, “I consider it quite as much an artistic production as the abomination” in one of James’ illustrations (see this illustration). Moreover, a correspondent in Madras, India, comments on James’ illustration of the Rubāʿīyāt, calling it “absolutely absurd”, while another from another city in India, Assam, comments on the “extraordinary accuracy” of the images (583).

James’s images present intriguing interfaces to the ways in which Victorian Orientalism received Khayyām. I detect a contestation in them that lays bare an inherent tension between belief and unbelief.

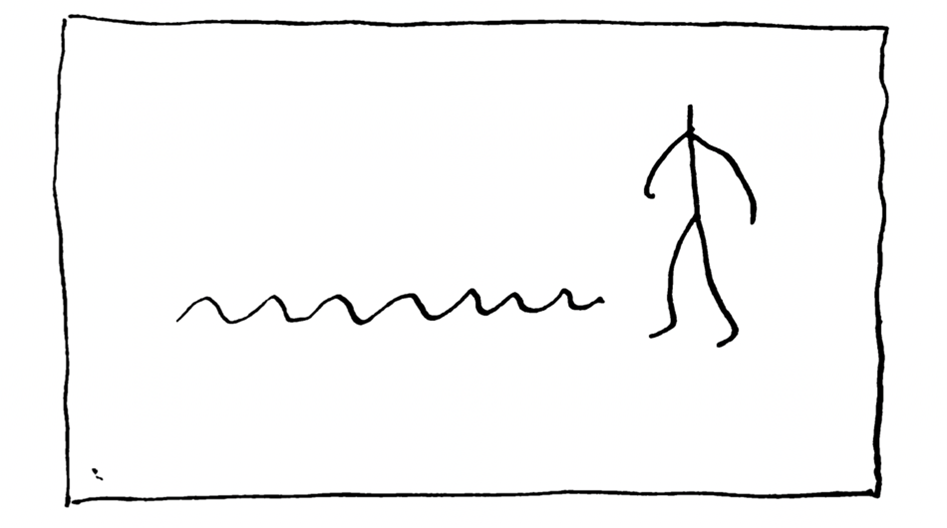

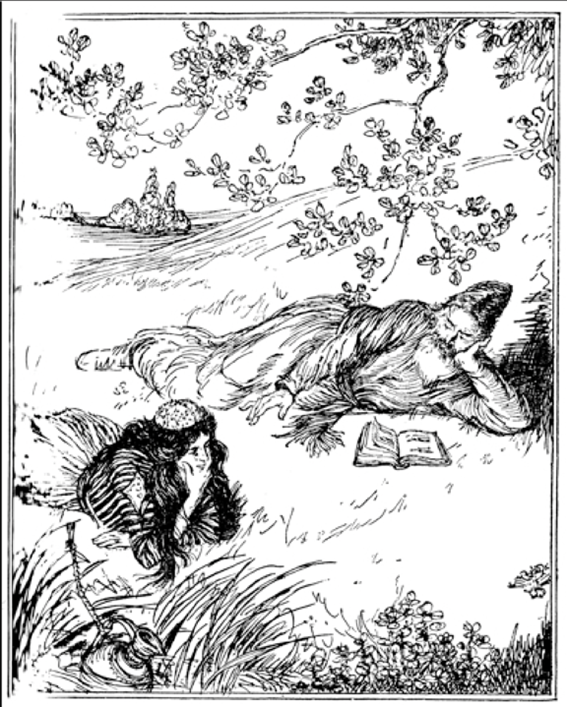

Let me get closer to the illustrations and elaborate on how this tension figures. Most superficially, James’ visualisation shows a semiotic tendency common among almost all the contemporaneous illustrations. A recurrent semiotic feature in this pattern is an indexical relationship between language and the image. As seen in Figure 2, icons and symbols link up directly with the poems’ semantics. If, for instance, the poems mention pleasure, the images depict female figures, wine cups, or vineyards. If roses are mentioned, we see iconic representations of roses, and so on. This happens in almost all illustrations of the Rubāʿīyāt before James. From the texts to images, icons and symbols are retrieved from familiar percepts in the mainstream Orientalist imagination. Most discernibly is the figure of the Muslim man, very often depicted with the cliché of the Fez hat (see this illustration), the Fez-man.

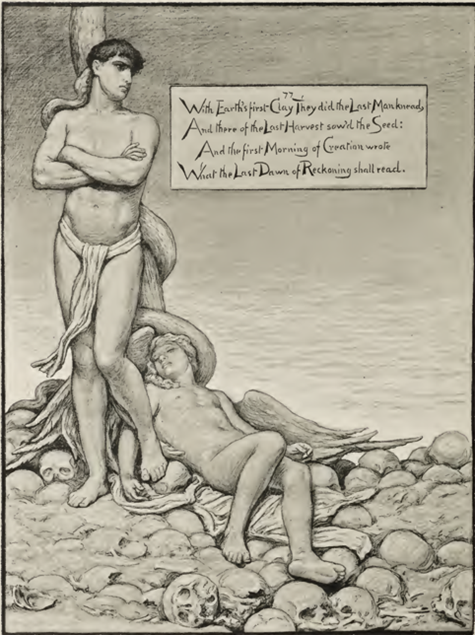

However, James’ artwork differs from most of the other Oriental representations at the time. First, the distortion of perspective should be mentioned. James’ illustration unsettles the photographic logic in most orientalist representations. The effect is outlandish for some people while alluring for others. One kind of audience would most likely feel comfortable viewing the image in Figure 3a but would perhaps not quite feel the same with Figure 3b, although both drawings refer to the same quatrain and use the same icons.

But there is also something happening on the level of narrative. James’ illustrations are the only ones among his peers that provide a sense of narrative continuity across the images. This is evident in the repetition of the figure of the Fez-man in almost all his illustrations of the Rubāʿīyāt. Always depicted with the same lack of facial expression, the figure moves from one frame to another, hence replicating FitzGerald’s narrative translation of Khayyām. He walks from one image to another and witnesses the passing of time. This figure is central to making a Victorian subject.

His subjectivity revolves around a tension between belief and unbelief. In every possible seriality of James’ images, there are implicit unresolved questions about life and death. These questions are not about the nature, or the origin, of things, they are not ontological nor epistemological, but rather pragmatic. In every image, the Fez-man asks, “What do I do?”, “How do I leave?”, “Where am I going?”, and in some images, we almost hear him asking, “Will there be life after death?”. And each question is asked with a sense of doubt, uncertainty, and even anxiety, most starkly depicted in the picture of the Fez-man in the pottery workshop (See this illustration). In one image, the Fez-man ascends to another world and meets the angel that one of the pious quatrains mentions (See this illustration). The angel is a bizarre mix of incompatible visual icons: a turban, a colourful robe, a pot, and wings. This final episode can be viewed as a decisive moment in the narrative. So, is there life after death? The Fez-man does not seem to be convinced, given his unchanged body pose.

References

Lawrence, Arthur. “Mr. Gilbert James and His Work”. The Idler. Vol. XVI. August 1899- January 1900. pp. 577-587.

© Arash Ghajarjazi and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2023. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Arash Ghajarjazi and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.