Rūmī’s story about Moses and the shepherd is one of the most popular stories from the Masnavī. It appears in anthologies, it has become the subject of various operas, and even features on websites with ‘Rūmī quotes’. Nowadays, the story is known as a clear example of Rūmī’s tolerance towards believers of different faiths and his role as a champion of religious pluralism. But how does the story fit into the context of Rūmī’s philosophy? And how does Rūmī’s message of love and tolerance relate to the Islamic intellectual tradition of his time.

| چارقت دوزم کنم شانه سرت | تو کجایی تا شوم من چاکرت |

| شیر پیشت آورم ای محتشم | جامهات شویم شپشهاات کشم |

Where are You, that I may become Your servant,

That I may sew Your shoes and comb Your hair?

That I may wash Your clothes and kill Your lice,

And bring Your milk to you, Your Eminence.

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, Book II, pp. 109-110, lines 1725-1726)

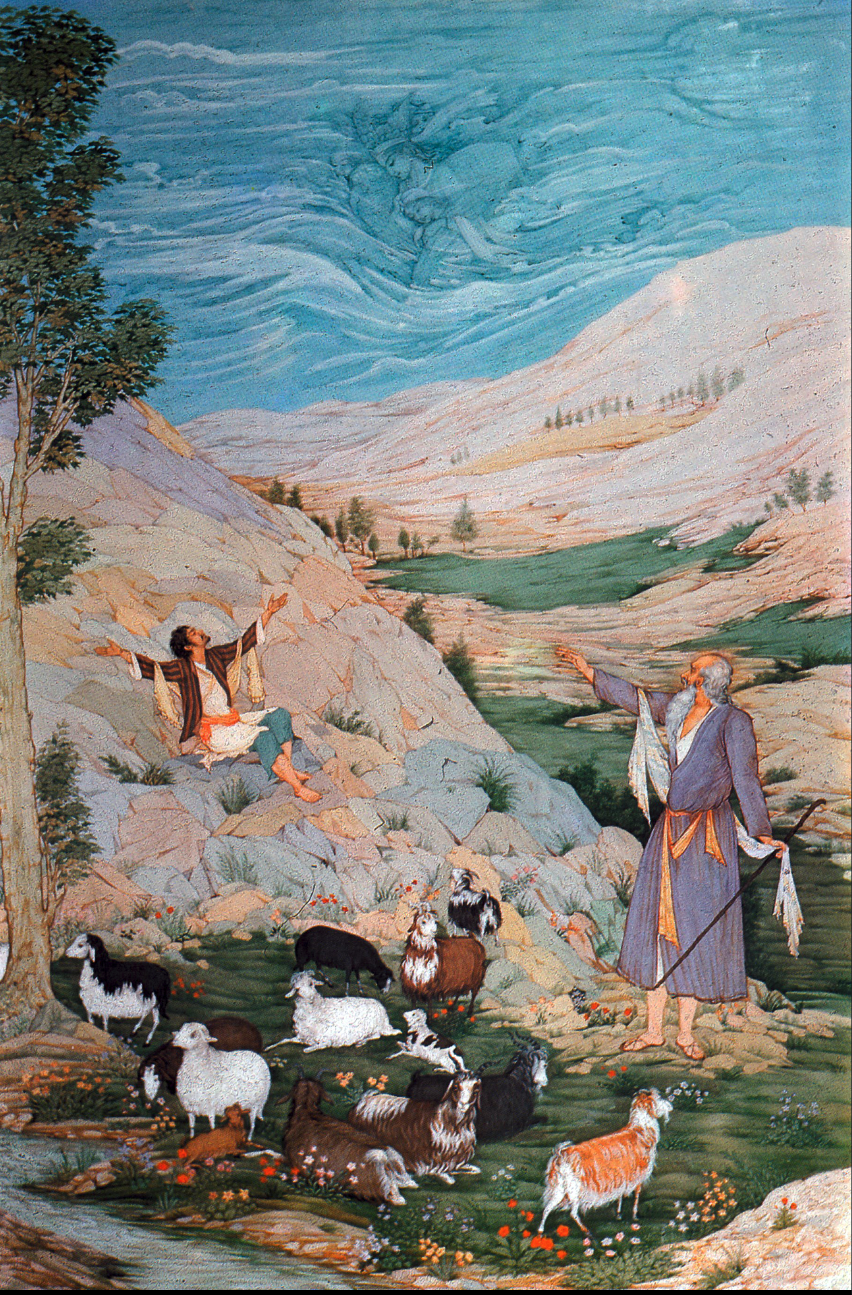

These are the first words of the shepherd in one of the most famous stories of Rūmī’s Masnavī. In the story, Rūmī depicts Moses as a prophet, one of the main characters in the Masnavī, as an orthodox theologian who reprimands a simple shepherd for speaking about God in a simplistic way. As can be read in the first lines of the story, the shepherd expresses his devotion to God in an anthropomorphic fashion and asks, among other things, whether he can ‘comb God’s hair’ and ‘wash God’s clothes’. Moses cannot believe this blasphemous words, ordering him to stop, but Rūmī would not be Rūmī if it did not eventually become clear that Moses is at fault here and not the shepherd.

In addition to broad message of religious tolerance the story proclaims, there is more to be said about the way this story is situated in the heated theological debates of the time. An important question is: is the relationship between humans and God based on fear of God and the reward and punishment of the afterlife, or based on love for God? Since the advent of Islam, many theologians emphasised the fear of God. From the ninth century onwards, however, a movement emerged that argued that God could also be approached through love. And since love is personal for everyone, this meant for the poets within this literary movement that Islamic theologians should not dictate to others how God should be worshiped. Rūmī makes no secret of his opinion. According to him, the relationship between man and God is a relationship of love, and no one has the right to criticise someone’s personal relationship with God.

The ‘lover’ of God is opposed to the rigid theologian Moses

After the shepherd’s intimate praises to God, Moses rebukes the shepherd for speaking to God in such a disrespectful manner. Moses calls him a kāfir (“infidel”) and orders him to put some cotton in his mouth so that he will stop talking. However, God hears Moses and rebukes him for criticising and sending away His loyal servant and worshipper. He asks Moses:

| یا برای فَصل کردن آمدی؟ | تو برای وصل کردن آمدی |

| اَبْغَضُ الْاَشْیاء عِندي الطَّلاق | تا توانی پا مَنِه اندر فَراق |

Did you come to create a sense of union,

Or did you come to generate division?

Do not touch separation if you can,

“For Me the worst of all things is divorce.”

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, Book II, p. 111, lines 1755-1756)

In His rebuke of Moses, God emphasizes that He is not interested in outward forms of worship or in the way people express their devotion. It is the sincerity of the heart that matters:

| ما روان را بنگریم و حال را | ما زبان را ننگریم و قال را |

| … | |

| سوز خواهم سوز، با آن سوز ساز | چند ازین الفاظ و اضمار و مجاز |

| سر بسر فکر و عبارت را بسوز | آتشی از عشق در جان بر فروز |

We look at neither languages nor words,

But at the soul and at the inner state,

…

How much more verbiage, tropes and metaphors?

I want your burning, burning! Warm to burning!

Inflame a fire of love within the heart!

Incinerate all thought and all allusion.

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, Book II, p. 112, regels 1763;1766-1767)

In Moses’ rebuke, God also makes clear that He is disinterested in outward forms of worship and every person worships Him in his/her own way:

| هر کسی را اصطلاحی دادهام | هر کسی را سیرتی بنهادهام |

| … | |

| سندیان را اصطلاح سند مدح | هندوان را اصطلاح هند مدح |

I have consigned a way for every one

To every one a different idiom.

…

For Hindis, Hindi is for praise of God:

The Praise of God in Sindi is for Sindis.

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, Book II, pp. 111-112, lines 1757; 1761)

After God rebukes Moses, he realises his mistake and runs after the shepherd to deliver God’s message. But when he finds the shepherd alone in the desert, Moses realizes that the man has undergone an inner, spiritual transformation. The shepherd has reached the highest stages of mystical insight and has been transformed into a ‘lover’ or walī (“Friend of God”).

In such lines of poetry in which Rūmī speaks about lovers of God, he emphasises the importance of love as the only instrument to know God and coming closer to Him, since words cannot express the experience of the Divine. For example, the shepherd emphasises: “Now my condition is beyond description / The things I say are not about my state.” (Masnavī, Book II, p. 83, line 1795). Because words fail to express, Rūmī urges his readers to “Inflame a fire of love within your heart / Incinerate all thought and all allusion.” (Rūmī, Masnavī, Book II, p. 112, line 1767). The “lover” of God is opposed to the rigid theologian Moses, who is convinced of his own way of worshiping, and who rebukes others for their blasphemous utterances. Only after God’s rebuke does Moses understand that the shepherd has become a ‘friend’ or walī of God through his sincerity and burning love.

Rūmī’s involvement in the Islamic intellectual discussions of his time

Rūmī’s introduction to the story of Moses and the Shepherd provides clues to how we can interpret the story. Rūmī announces the story as “The criticism of Moses – peace be upon him – on the prayers of the shepherd.” The word for “prayer” that Rūmī uses here is munājāt (“intimate, fervent, personal prayers addressed to God”), a word that refers to a genre in the Persian literary tradition in which mystics composed personal prayers to God in poetic form or rhythmic prose. This genre became popular at the time of discussions among Islamic scholars about how God should be worshiped and what role love plays in it. In a munājāt the poet often positions himself as a lover of God, and God is seen as the beloved. The personal relationship is emphasized.

Another informative element in the introduction is that, prior to the story of Moses and the shepherd, Rūmī explains the different ways in which God is worshiped:

| اندر آتش دید ما را نور داد | اذکروا الله شاه ما دستور داد |

| نیست لایق مر مرا تصویرها | گفت اگرچه پاکم از ذکر شما |

| در نیابد ذات ما را بی مثال | لیک هرگز مست تصویر و خیال |

| وصف شاهانه از آنها خالصست | ذکر جسمانه خیال ناقصست |

| این چه مدحست این مگر آگاه نیست | شاه را گوید کسی جولاه نیست |

‘Remember God,’ our sovereign gave permission,

He saw us in the fire and gave us light.

He said, ‘Though I am free from your remembrance,

And images are not conducive to me,

Yet one who’s drunk on images and fancies

Will never find Our Essence without symbols.’

(Rūmī, Masnavī, trans. Williams, Book II, p. 109, lines 1719-1723)

According to Rūmī, most people express their love for God by attributing human qualities to God, and they try to make a relationship with God in their own language.

Man’s shortcomings are a common thread in Rūmī’s poetry. We know Rūmī through his beautiful Persian poems, which have been translated into many languages and have touched people all over the world. But Rūmī himself is often critical of his own poetry and his use of this poetic language to describe his love for God. He often emphasises the futility of his own poetry and regularly ends his poems with the word khāmūsh (“silent”).

In his poetry, Rūmī frequently emphasises the high status of the Friends of God, and the importance for other mystics to follow these Saints on the path towards God. According to Rūmī, the Friends of God are those closest to Him and whose actions are based solely on His divine command, even if it results in breaking the law. In this way, Rūmī argues that mystics who have been transformed into Friends of God are not bound by the legal requirements of Sharia. They are above dogmas and religious laws. However, the Rūmī scholar Jawid Mojaddedi notes that we should not conclude from this that Rūmī is indifferent to people who violate religious laws. On the contrary, people who are not focused on the mystical path and do not possess the knowledge of a Friend of God are certainly not allowed to break the law, because they are motivated only by their nafs (“baser self” or “egocentric impulses”).

The high status of the Friends of God is also evident in the story of Moses and the shepherd. Believers who base their knowledge of God on the concept of Love and who attain higher levels of mystical vision, according to Rūmī, transcend temporal and earthly contradictions such as belief and disbelief, the sacred and the profane, obedience and disobedience; usually the subjects of religious law. According to Rūmī and other mystics, these categories cease to have meaning when the mystic reaches his or her destiny, i.e., God. After Moses tells the shepherd that he has permission from God to praise Him in his own words, the shepherd explains that he has passed the point of belief and unbelief and has experienced God’s true knowledge that he cannot express in words.

In the story of Moses and the shepherd, Rūmī describes a tension between adhering to religious laws on the one hand, and reaching higher stages on the mystical path on the other, where concepts such as belief and unbelief are not relevant anymore. Where Moses calls the shepherd a kāfir (“heretic” or “infidel”) at the beginning of the story after hearing his intimate prayers, the shepherd tells Moses at the end of the story: “I have passed that point, now I am soaking in my heart’s own blood.” (Rūmī, Masnavī, Book II, p. 114, line 1791). In this way, the shepherd states that he has become a lover of God. The shepherd’s love is symbolised by his bleeding heart, and he has gone beyond the point of ‘belief’ and ‘unbelief’. It shows that Rūmī also involved himself in the Islamic intellectual discussions of his time with the story of Moses and the shepherd. He presented the different positions in this debate through the rigid theologian Moses and the simple shepherd who addresses God in loving terms. Discussions within the medieval Islamic tradition gave Rūmī the inspiration for the story about Moses and the shepherd. It is a story that continues to inspire people around the world to this day through the message of tolerance it proclaims.

This English blog is a modified version of my presentation at Rumi symposium at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), 20 December 2023. A longer Dutch version of this piece is published in the special issue of ZemZem: tijdschrift over het Midden-Oosten, Noord-Afrika en islam (2/2023) devoted to the Persian poet Jalal al-Din Rumi.

Cited Works

Lewisohn, Leonard, “Sufism’s Religion of Love, from Rābi‘a to Ibn ‘Arabī.” In Lloyd Ridgeon, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Sufism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2014, 150-180.

Mojaddedi, Jawid, Beyond Dogma: Rūmī’s Teachings on Friendship with God and Early Sufi Theories. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pourjavady, Nasrollah, “The Concept of Love in ‘Erāqī and Aḥmad Ghazzāli.” In Persica 21 (2006-2007): 51-62.

Rūmī, Jalāl al-Dīn, The Masnavī of Rūmī, Vol. II. Translated by Alan Williams. London: I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2020.

Shafīʿī Kadkanī, M.R., Dar hargiz u hamīsha-yi insān: az mīrāth-i ʿirfānī-yi khvāja ʿAbd-Allāh Anṣārī (Tehran: Sukhan, 1394/2015).

© Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2024. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Maarten Holtzapffel and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.