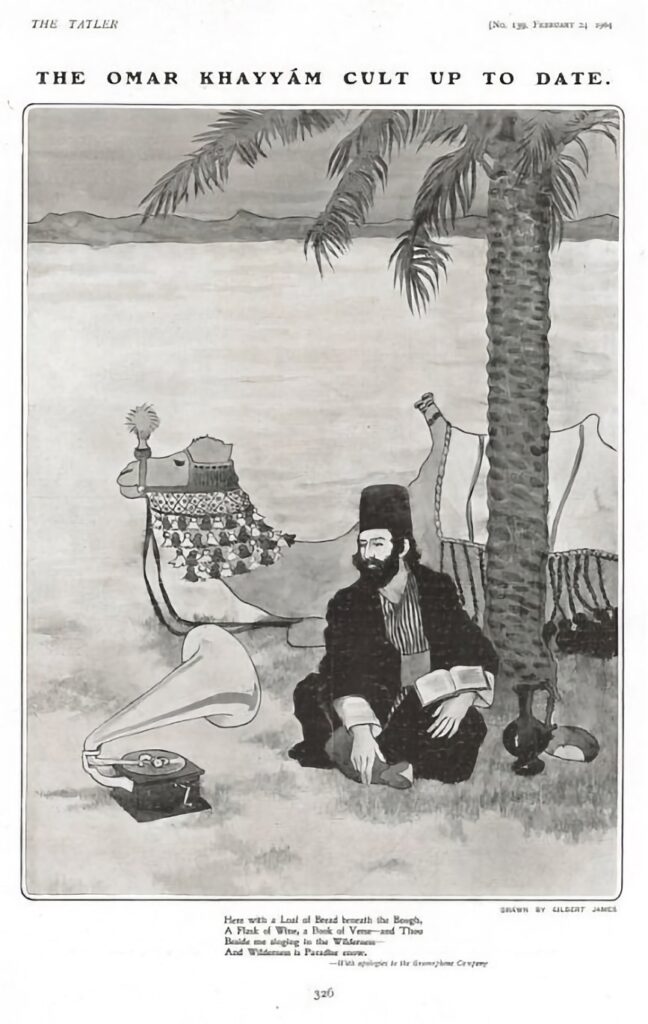

When I published the poster for my upcoming book talk on “Remembering Khayyam in Modern Iran,” I anticipated that some might raise an eyebrow at the design choice. The illustration depicts a man wearing a fez hat, seated under a palm tree, with a camel resting behind him as he appears to be listening to a phonograph. It is a deliberate collage of Orientalist stereotypes. I want to explain why this seemingly stereotypical image serves a critical purpose. Here is a reproduction of the original image:

The illustration comes from a 1904 issue of the British periodical The Tatler. I purchased its copyright specifically for my Khayyām project because it captures an essential part of my research (Ghajarjazi 2025: 210). Created by the British artist Gilbert James (d. 1941), this image was originally a humorous commentary on the London Club of Omar Khayyam, a group of Rubáiyát-lovers and FitzGerald’s fans, whose interest in Khayyam embodied a host of Orientalist contradictions.

James was no ordinary illustrator. As I explored in my book and a previous blog post, his Khayyam illustrations stood apart from the typical Orientalist art of the period. While most Victorian Orientalist artists depicted the “East” with the old and dull attention to perspective and anatomical idealism, James broke these conventions. His two-dimensional, abstract style was both praised and reviled by contemporaries, who found his work either refreshingly modern or shockingly “obscene” in its departure from artistic norms.

What makes this illustration so fascinating is the juxtaposition of Oriental clichés with a modern technical object. The phonograph, a relatively new sound technology of the early 20th century, sits incongruously alongside the timeless desert scene. Above the image, outside the frame, the first caption reads, “The Omar Khayyām Cult Up to Date”, and below, the second caption quotes the most popular Omarian quatrain of the Victorians, the eleventh quatrain in FitzGerald’s first edition:

Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough,

A Flask of Wine, A Book of Verse–and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness–

And Wilderness is Paradise enow (As cited in Ghajarjazi 2025: 210).

The illustration seems to be asking: how could a group of people – much like a cult as the club was commonly called at the time and with nearly no knowledge of Persian language – be fascinated by a Persianate persona from medieval times and at the same time profess a sense of secular modernity through that fascination? A quick note on the secular: we know that Khayyām was a recurrent figure in debates on religion and science in Victorian England. We also know that many Christian authorities routinely attacked Khayyām lovers in England for their irreligiosity, callous [sic] understanding of poetry and history, and missing the “hidden” piety in Khayyām. The Victorian periodical press contains numerous records about these attacks and reflects how controversial the name Khayyām was in English mass media (Ghajarjazi 2025: 172-3). James understood this tension, and his illustration reflects that.

In his “The Omar Khayyām Cult Up to Date” image, he gently mocks those British enthusiasts who, despite knowing nothing of Persian language or culture, revelled in an imaginary Persian persona that represented for them a new kind of modern sensibility and this-worldliness. Placing a camel, a palm tree, and a bearded man wearing a fez hat is James’ way of playfully mocking the Orientalist fantasies of Persia, all-too-familiar visual clichés whose placements inside the image border on caricature. The phonograph, meanwhile, adds a sly nod to the mediated nature of this imagination: Persia not as it is – to recall Charles Will’s (d. 1912) horribly Orientalist book title (Wills 1886) – but as it is represented at the early age of mass media. Placing the image next to the captioned quatrain, James seem to note how the Orientalist Khayyām-lovers, “with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough, A Flask of Wine, A Book of Verse”, and the absent “Thou”, are “singing in the Wilderness”, as part of a fantastic cross-continental and transhistorical auditory experience made possible by a phonograph. James shows us how absurd this Orientalist love for Khayyam is.

But even more interesting for me was that a similar sense can be recognised in the 1920s among modern Iranians who were re-introduced to Khayyām rather late owing to this Victorian, and later global, fascination with Khayyām. Much like the London Club, many Iranians, from the Berlin diaspora communities to Iranian Pahlavi state officials in Tehran, doted on an imaginary persona – assumed to be a real mathematician-physician-ḥakīm-imām-philosopher-poet, despite all contradictory and limited anecdotal evidence – and re-portrayed Khayyām as a national heritage. Many artists and writers, such as Sādiq Hidāyat (d. 1951), though later in his career, were suspicious of this fantastical retro-nationalism.

So why use this stereotypical image for my book talk? Because the camel, that hackneyed Orientalist figure, has analytical value. It gives a brief but powerful image of the historical and cultural processes through which Khayyām was remembered and reimagined, both in the West and in Iran. James’s illustration both participates in and critiques Orientalism by clever composition and design choices. For a hasty eye, and especially the kind of eye that is still bent back on “the glorious past of Persia” – for the kind of eye that, as Iranian philosopher Ārāmish Dūstdār (d. 2021) said, “longed to inherit the legacy of the ancient Iranians and choked by resentment over defeat by Islam” (Dūstdār 2019: 20) – the camel is immediately offensive. For this hasty eye: “Of course! We are not camel riders,” or in the more racist formulation, to quote a popular slogan chanted quite recently in 2025 at the tomb of Omar Khayyām during a mass celebration of Nawrūz, “We are Aryans! We don’t worship Arabs”. The poster aims to draw attention to this aspect of Iran’s modern history, eliciting an emotional response from the hasty onlookers to show them the longer and complicated history that informs their immediate emotional response.

References

Dūstdār, Ārāmish. Introduction to Pseudolanguage and Pseudoculture (Zabān u shibheh zabān: Farhang-e shibeh farhang). Köln: Forough Publishing, 2019.

Ghajarjazi, Arash. Remembering ʿUmar Khayyām: Episodes of Unbelief in the Reception Histories of Persian Quatrains. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2025.

Katouzian, Homa. Sadeq Hedayat: The Life and Legend of an Iranian Writer. London: I. B. Tauris, 2022.

Wills, Charles James. Persia as It Is, Being Sketches of Modern Persian Life and Character. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington, 1886.