ʿAbdulḥusayn Ṣanʿatīzāda Kirmānī (d. 1973) was one of the lesser-known modern Iranian writers. He is remembered for his novellas such as Majmaʿ-i Dīvānagān and Mānī-yi Naqqāsh. He is also known as the author of the first modern science fiction in Persian literature, Rustam in the 22nd Century, which was first published in 1934. The novella imagines a utopian Iran in the distant future, where Shāh-nāma’s (The Epic of the Kings) epic hero, Rustam, is resurrected by a fantastic machine. This blog reads a few excerpts from the novella that reflect the implication of such a modern resurrecting machine for Muslim belief.

The novella Rustam in the 22nd Century has been remembered as the first Persian work of science fiction that invents narrative strategies to engage with and reflect on the Iranians’ struggle with Pahlavi modernisation in the 1930s. Serialised in the periodical Shafaq-i Surkh in 1934, it blends classical Persian themes with futuristic visions to creatively comment on what it would mean for Iranians to live in a future utopia where everyone can fly with personal wings, watch the “volcanos on the moon through giant telescopes”, enjoy immersive 3D cinema, and watch and be watched by others live at any time through two-way television screens. This 22nd-century utopia is disrupted when Rustam, the legendary hero of Firdowsī’s Shāh-nāma, is brought back to life by a resurrecting machine: a new invention that could revive the dead.

Despite being overlooked in the modern Persian literary canon – most likely due to its perceived amateurish approach to a genre that never gained substantial traction in Persian literature – the novella was a contemporary success. Its writing is often criticised for its crude descriptions, simplistic plot, flat characters, and poorly crafted dialogues. Yet, it resonated with readers and prompted the release of a third edition with original illustrations in 1937. Esteemed literary figures, including Nīmā Yūshīj (1895-1960), the vanguard of Persian modern poetry, and Muḥammad ʿAlī Jamālzāda (d. 1997), a key figure in Persian modern short fiction, commented on the work; Jamālzāda even wrote the preface for the third edition (Ṭāhbāz 1997, 571-577; Ṣanʿatīzāda 1937, 1-7). Despite its literary shortcomings, the novella’s appeal lies in its bold departure from convention. It went beyond its social and political context by introducing an unfamiliar genre to Persian literature and thus ensured its continuous reception in Persian. Ṣanʿatīzāda was among the early contributors to the emerging wave of utopian and dystopian literary creativity of the time, alongside contemporaries like Ṣādiq Hidāyat (d. 1951), whose short story “S.G.L.L” similarly engaged with the technological advancements of modern Iran (Pedersen 2015: 190–195).

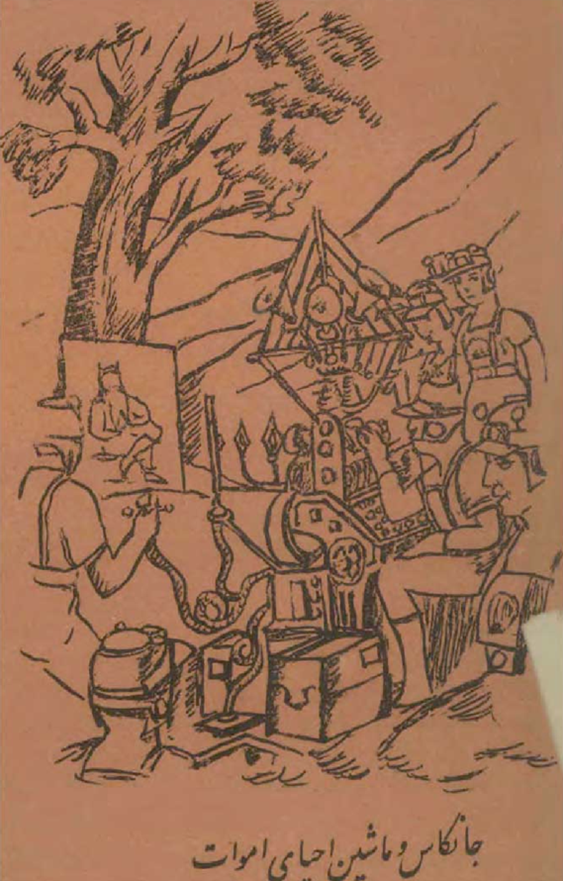

Rustam in the 22nd Century came a decade after his better-known work, The Assembly of Lunatics (Majmaʿ-i Dīvānagān), published in 1924 with a similar interest in futuristic imagination but less attention to technological imaginaries (Pedersen 2007; 2015: 190; 2016: 89-109). The novella’s central appeal stems from its utopian vision: a technologically advanced Iran, which extended the early 20th-century Iranian modernisation to absurd limits. Society enjoys astonishing innovations in visual media, including video telephony – which might have been an allusion to Albert Robida’s “telephonoscope” in his 1890 novel La Vie Électrique. The resurrecting machine, however, unsettles this perfect society. This “machine for materialising the spirits and bodies of the dead” is invented by an obscure and vaguely named Mr. Jankas (Jānkās). The novella’s opening scene describes Jankas and his pupils operating the machine for the first time in what used to be the Sistan province in the 20th century, also Rustam’s birthplace. They set up the device next to a tree, which comprises a white screen, three wires, and a cluster of noisy components (Figure 1). The machine then materialises Rustam and his imaginary squire called Zingiyānū. During their outlandish stay in Iran’s utopian capital, the Quixotic couple encounter unprecedented technologies and become targets of ridicule for their social ineptitude, lack of sophistication, and adherence to traditional values. Their short adventures culminate in their arrest by the “Chief of Regulation (Raʾīs-i tanẓīmāt)” and together with Jankas, they are all put on trial. It is in the trial scene that the novella stages the religious anxieties about modern technologies in Iran.

At a certain point during the trial, Jankas is put on the stand and is interrogated by the public prosecutor. He calls Jankas a charlatan and argues:

I, who have spent years studying the science of the spirit (ʿilm al-rūḥ), after conducting scientific enquiries into the machine that Jankas claims to have invented, have concluded that his assertions are baseless. Therefore, I strongly refute Jankas’s so-called invention. There is no doubt that this individual has masqueraded two living people to appear in such strange and peculiar forms and deceive ignorant and uneducated individuals into believing that he can bring the dead back to life, just to gain fame. According to all scholars of the science of the spirit, when the soul departs from the body’s cage, it may ascend to a higher and more exalted state (maqāmī aʿlā-tar). However, it is impossible for it to descend once again and inhabit its original form, which has disintegrated, with each particle becoming part of another being. Therefore, it is crucial to verify and prove the authenticity of Jankas’ invention (98).

In his response to the prosecutor, Jankas goes into a long lecture about materialism and evolution. He rejects the existence of spirits and argues that the body is the outcome of natural processes that begin on the atomic scale. But how can the dead be resurrected according to this materialist logic? Jankās responds with an imaginative twist in his materialism:

You surely know that the boundless expanse of the sky serves as a repository of sounds, preserving every voice within it for eternity, like pages in a book. Today, we know that the voices of all people who have ever lived remain in the atmosphere, undisturbed and intact, alongside the sounds that came afterwards. Thus, when I intend to revive the dead, I follow these steps:

1. Determine the century and year in which the deceased lived.

2. Identify the language they spoke.

3. Pinpoint the region of the world where they resided.

Once these details are known, locating the desired layer of existence, where the individual is contained, becomes much easier (98-99).

The dialogue between Jankas and the public prosecutor was not unfamiliar to the Iranian public. Discussions about Spiritualism in this period were already widely circulated in the periodical press, where readers could marvel at how Spiritualists like the famous Khalīl Saqafī (d. 1944) summoned the dead in their séances, calling in figures like Ḥāfiẓ and Khayyām (Ghajarjazi 2025, 247-249). Jankas’ resurrecting machine pushed this cultural infatuation to an absurd limit – if Spiritualist séances were not already absurd enough. His resurrecting machine revealed a profound tension and confusion between debates about materiality and spirituality in the Pahlavi Iran. The prosecutor challenges the plausibility of Jankas’ invention by recourse to the notion that spirits could never return to the body after death and will instead step into a more “exalted state (maqāmī aʿlā-tar).” In contrast, Jankas rejects the idea of spirits – though Ṣanʿatīzāda uses the term “materialising the spirits and bodies of the dead” to refer to the resurrecting machine – and represents what we might recognise today as reductionist materialism, whereby natural sciences are considered sufficient for explaining the phenomenal world. While Ṣanʿatīzāda’s figure of Rustam becomes an allegory for Iranians’ struggle to reconcile “tradition” and “progress”, his resurrecting machine represents the troubled relationship between “old” and “new” sciences. It was no coincidence that in his letter to Ṣanʿatīzāda, Nīmā Yūshīj praises the novella precisely for bringing this tension into view, which I quote below as the concluding paragraph of this blog. Yūshīj finds the novella alluring and says:

If phrases like “spirit among billions of spirits of the dead” and the like, which give a scent of idealism did not undermine the foundation of the allure, human power would have acquired its true, that is, material, aspect and would have been presented in a manner more acceptable with the materialistic mindset that is a necessity of modern thought. In other words, the concept of “spirits of the dead” fundamentally contradicts the premise of the belief that human power can become the highest of powers. This is because such power, to the extent that it draws our attention, results from material superiority and domination over the material world. With the recognition of this power, the connection between humans and spirits who have continued their lives for years and centuries becomes worth considering, in terms of how such a connection might be possible (Ṭāhbāz 1997, 571-572).

Figure 1. Illustration of Jankas’ resurrecting machine, featuring three loudspeakers at its center and a canvas displaying Rustam’s image on the left, positioned against a tree. The Persian caption reads, “Jankas and the machine of reviving the dead”.

Cited Works:

Ghajarjazi, Arash. Remembering Umar Khayyām: Episodes of Unbelief in the Reception Histories of Persian Quatrains. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2025.

Pedersen, Claus Valling. “San’atizâde’s Majma’-e Divânegân, ‘An Assembly of Lunatics’: The Earliest Utopia in Modern Persian Literature,” Folia Orientalia, vols. XLII–XLIII (2007): 137–44.

Pedersen, Claus Valling. “Utopia and Dystopia in Early-Modern Persian Literature: Representations of the Advent of Modernity to Iran”. In Novel and Nation in the Muslim World: Literary Contributions and National Identities, edited by Elisabeth Özdalga and Daniella Kuzmanovic, 185–200. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Pedersen, Claus Valling. The Rise of the Persian Novel: From the Constitutional Revolution to Rezâ Shâh 1910-1927. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2016.

Ṣanʿatīzāda, ʿAbdolḥosayn. Rustam in the 22nd Century (Rustam dar qarn-i bīst u duvvum). Third edition. Tehran: Chap-i Markazī, 1937.

Saṭvatī Qalʿi, ʿAlī. Pāvaraqī yā rumān: Qānūn, taraqqī, va nāsīunālism. In Sīnimā u Adabiyyāt 14 (65), 2017: 218–221.

Ṭāhbāz, Sīrūs, ed. Complete Collection of Nima Yushij’s Letters. In Persian. Tehran: Nashr-i ʿilm, 1997.

© Arash Ghajarjazi and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2025. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403). Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Arash Ghajarjazi and the Beyond Sharia ERC Project.